It says a lot about 2020 that the worst pandemic in a generation is now only the second-biggest story in the world. After three months of withdrawing from society more comprehensively than any people in history, many of us have spilled out onto the streets to demand an end to white supremacy. Historians are just beginning to speculate about the ways the pandemic contributed to the material conditions for the current uprising. All the more reason to look back on the months before our society opened up again in a frenetic burst.

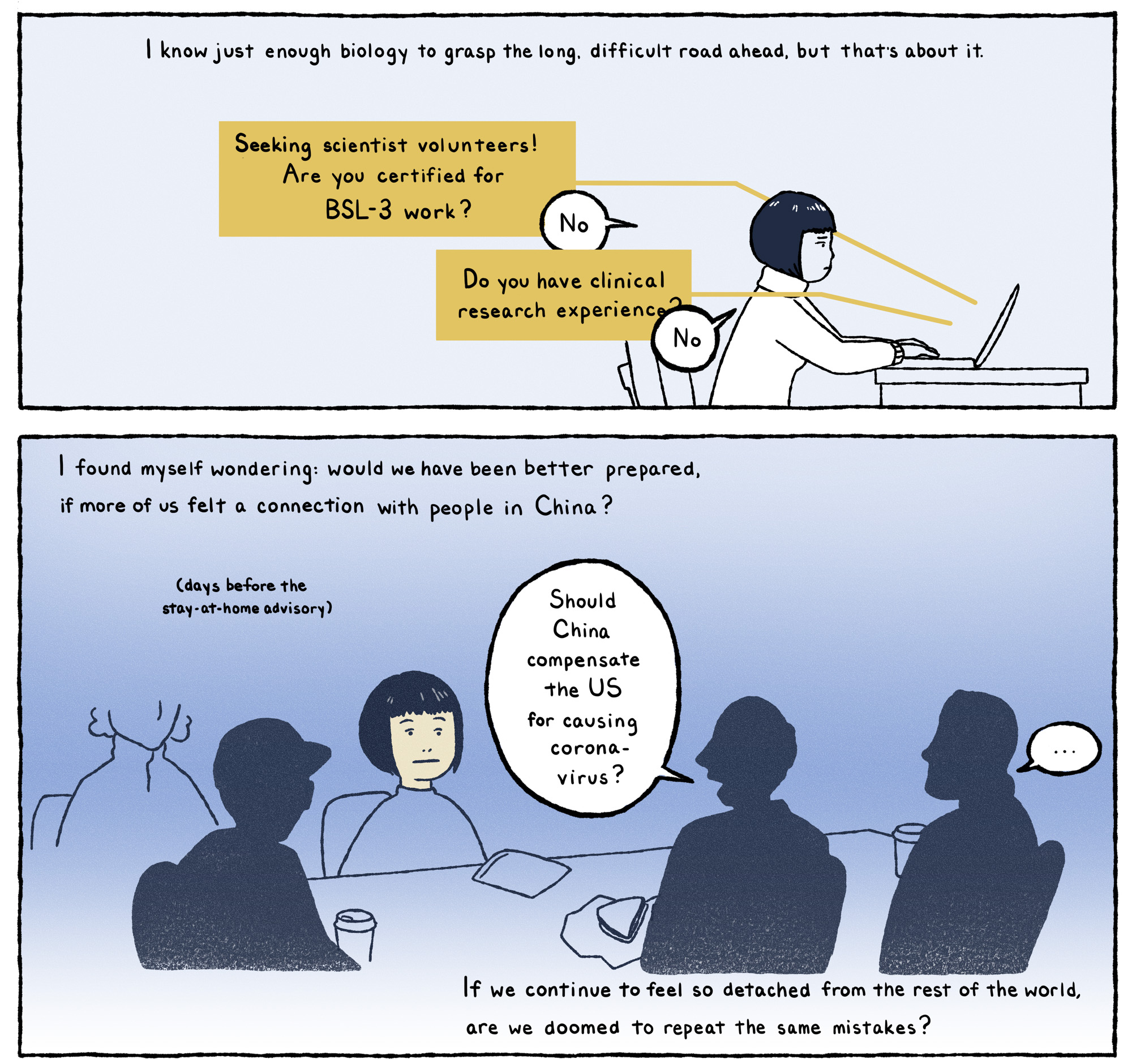

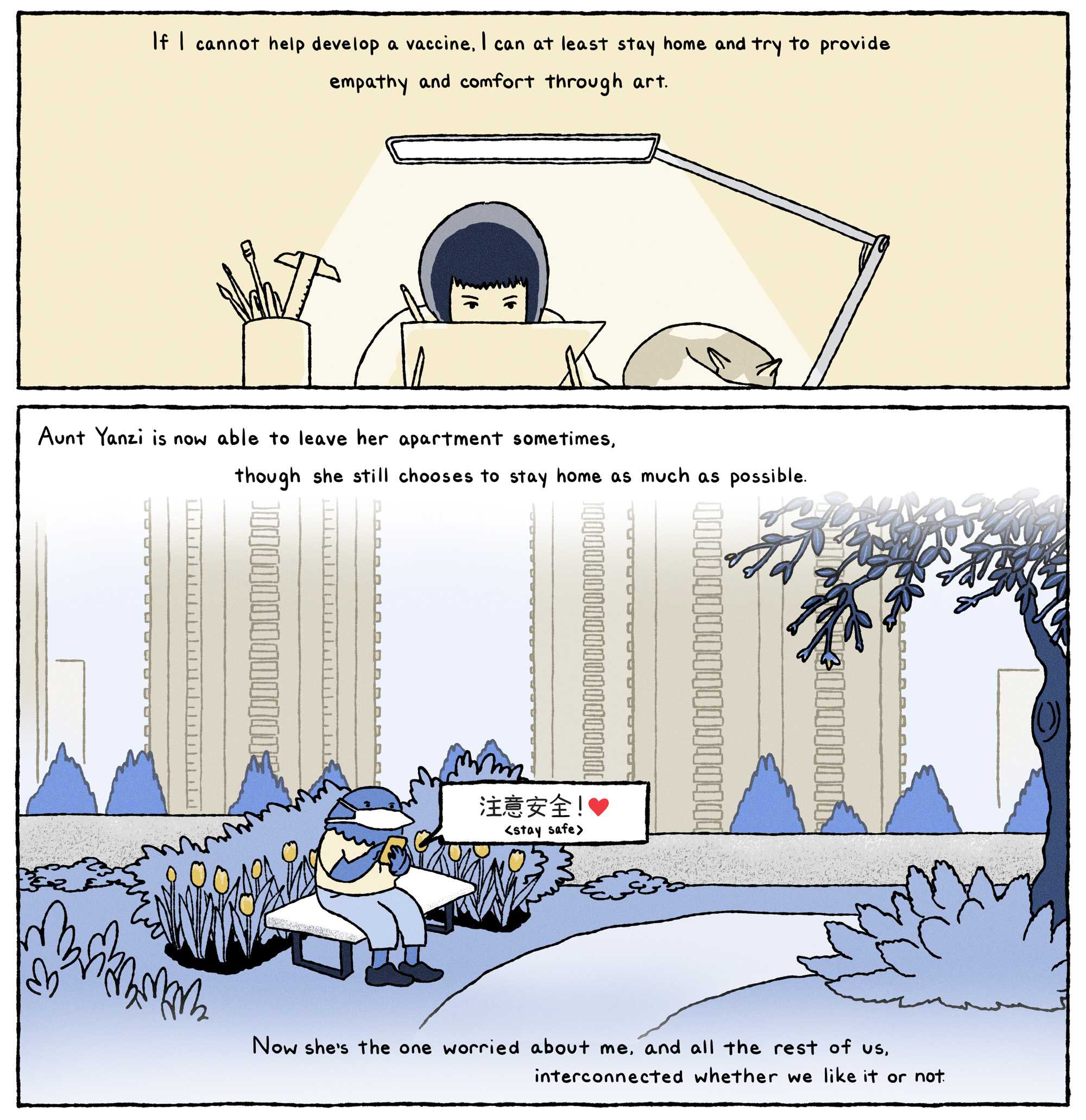

In the diaries below, composed between March and May, four scientists capture the new interior worlds created by COVID-19. Immunologist Zuri Sullivan reflects on what it means to be a Black scientist while two tragically complementary viruses are ravaging communities of color. Neuroscientist and comic illustrator Caroline Hu is reminded of her family in China, and how our new connectedness clashes with old disconnects. Cell engineer Shawdee Eshghi thinks about the relative privilege of social distancing. Yeast geneticist Sudeep Agarwala finds himself connecting more readily with the struggles of ancient history. These are testaments to how we got to where we are now, and the changing roles of science and identity in this new age of pandemics.

Twin Pandemics

BY ZURI SULLIVAN

The Early Days

Mounting alarm as my screen time more than doubles in the span of a week. I wonder how many messages I can send to my family’s group text before they stage an intervention. But at this point too much news feels better than no news because things are changing so quickly. And as an immunologist who follows many immunologists, virologists, and epidemiologists on Twitter (and the only member of my family who is a scientist or uses Twitter), I feel obligated to be the information ambassador. Every errand I convince my parents not to run is a small victory. I add their local newspaper to my rotation, nervously checking the number of cases in their area while wondering when their governor will issue a stay-at-home order.

My brother in New York City is eager to take my advice despite my long history as his know-it-all big sister. After six years of wondering what my thesis research will amount to, it feels good to know that my expertise is marginally valuable. A NYC-based friend with a mild fever and cough sends me a Google Doc where he’s been documenting his symptoms. I remind him that I’m not that kind of doctor (nor am I the other kind, yet, come to think of it). He’s also a scientist, so I send him some interesting pre-prints on the virus, and point him towards some of the Twitter immunologists/virologists/ epidemiologists that I follow. He later becomes my first friend to test positive for SARS-CoV-2, among several others with symptoms that have been unable to get tested.

Once stay-at-home orders have been issued across most of the country, I decide it’s time to turn off notifications from the New York Times app and dial down my Twitter usage.

Sleep Hygiene

Mid-March: I lie awake at night weighing the pros and cons of delaying my graduation and the start of my postdoc in order to wrap up my experiments whenever the lab shutdown is lifted. I mentally draft emails to my PhD mentor, my postdoc mentor, and the owner of the bar where I was planning to have my graduation party.

Late March – early-May: An elaborate (mostly) social media-free bedtime routine has become the bedrock of my mental health.

early-May – Present: A resurgence of the insomnia and anxiety I experienced in 2016, when I was haunted nightly by fears of one of my loved ones being gunned down for doing everyday activities while inhabiting a Black body.

New York City is Our Home

My great-grandmother moved to Brooklyn in 1920 during the Great Migration, a period in the early 20th century when millions of Black Americans fled the racialized terror of the South seeking refuge in the big cities of the North and West. These internal migrants subsequently faced Jim Crow segregation, housing discrimination, and the racist criminal justice system that persists to this day. In 1965, my then-6-year-old father immigrated to Brooklyn from Panama, along with his parents and two older brothers. In 2018, my younger brother moved to Harlem to work as an urban planner.

100 years after my family first put down roots in New York City, it has come to feel like my second home — a magical sanctuary I regularly escape to on the Metro North Railroad to visit friends, see a show, have a drink in a bar without worrying that I’ll be the only Black customer. My last pre-social distancing social memory was having brunch at a regular haunt in Park Slope with my brother and my uncle who’s been a Brooklyn resident for over 50 years.

It’s been horrifying and heartbreaking to watch the virus decimate the city. I’ve feared for the health and safety of my friends and relatives there. I’ve felt sad that I can’t visit, going on the longest stretch without visiting New York City since starting my PhD in 2014. And I feel devastated by how the pandemic has seized on a century of social inequality and disenfranchisement to so disproportionately affect the city’s Black and Latinx communities that represent my family’s origin story.

Graduating for the Ancestors

I start a 15+ person family group text to share my unsolicited two cents as the self-appointed family immunologist. I begin hosting a bi-weekly family Zoom happy hour to help ameliorate my own feelings of isolation. During one of these “get-togethers” my cousin asks whether she should still plan on traveling to New Haven for my thesis defense on June 26th, a date my entire extended family has had on their calendars since Christmas.

Fantasizing about my thesis defense has gotten me through some of my most challenging moments in graduate school. For years I’ve pictured the moment after my presentation, when I acknowledge my family, my ancestors, and trailblazers like Michelle Obama and Serena Williams who have been stand-in role models for the Black woman science professor I’ve never met. When I explain how it feels to be getting my PhD from Yale, after graduating from Harvard, only five generations removed from slavery. When I present my dissertation work to an audience that includes my grandmother who grew up hearing her great-grandmother’s stories about being emancipated from slavery in Virginia at age 14. The first time I’ll give a talk for an audience that includes more than one or two Black faces.

I attend a couple of remote defenses. Not as bad as I thought. I wonder what it will take for me to accept that the culmination of the 6 most challenging years of my academic life may turn out to be me alone in my studio apartment talking to my computer. That I won’t be able to look my parents and grandparents in the eye when I talk about what their sacrifices have meant to me. I postpone my defense, cross my fingers, and hope that things will work out.

We Shall Overcome

As March turns to April I’m unsurprised to learn about the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on communities of color. I fear for my boomer parents and octogenarian grandparents, for my brother whose job in New York City involves “essential” work that cannot be conducted remotely. I double down on my efforts as the family immunologist, firing off emails and group texts in the hopes that no one I love will become a statistic.

Books become a source of comfort as I turn to stories of our struggle. They remind me of what we’ve overcome in the 400 years since the first Black bodies were forcibly brought to the stolen land that later became the United States of America. Reading about the resilience of Black folks has become a standard coping mechanism when I feel like I’m living through a terrifying moment in history.

I hold a solo dance party to commemorate the 2-year anniversary of Beychella, where I witnessed Beyoncé’s history-making headline performance at Coachella that celebrated the beautiful struggle and rich cultural history of Black Americans. I tune into DJ D-Nice’s sets on Instagram live and jam alongside Michelle Obama and half a million others to the records I grew up hearing on my parents’ stereo. I watch the legendary Erykah Badu and Jill Scott bless the world with Black girl magic in an Instagram live battle; Michelle Obama is once again “in attendance.”

I have another celebration when the 2020 Pulitzer Prize awardees are announced and include Colson Whitehead for The Nickel Boys, Nicole Hannah Jones for her essay as part of The 1619 Project, and Ida B. Wells, posthumously, for her reporting on lynching in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

#Runningwhileblack is My Coping Strategy

A 21st century lynching appears on my Twitter feed. I watch as Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed, 25-year old Black man out for a jog is hunted down and shot by two white men. I learn that the murder occurred more than two months ago and that neither of the killers has been charged. I experience a million different emotions, but zero surprise. Science Twitter is more active than ever these days but says little about today’s horror. I wonder (as I always do when these things happen) how many of my fellow scientists have seen the video. If they feel as sick about it as I do. If it fills them with terror.

I feel more alone in this moment than I’ve felt over the past two months spent by myself in my studio apartment. I go on a run to process my thoughts, constantly looking over my shoulder.

How Far Away is China?

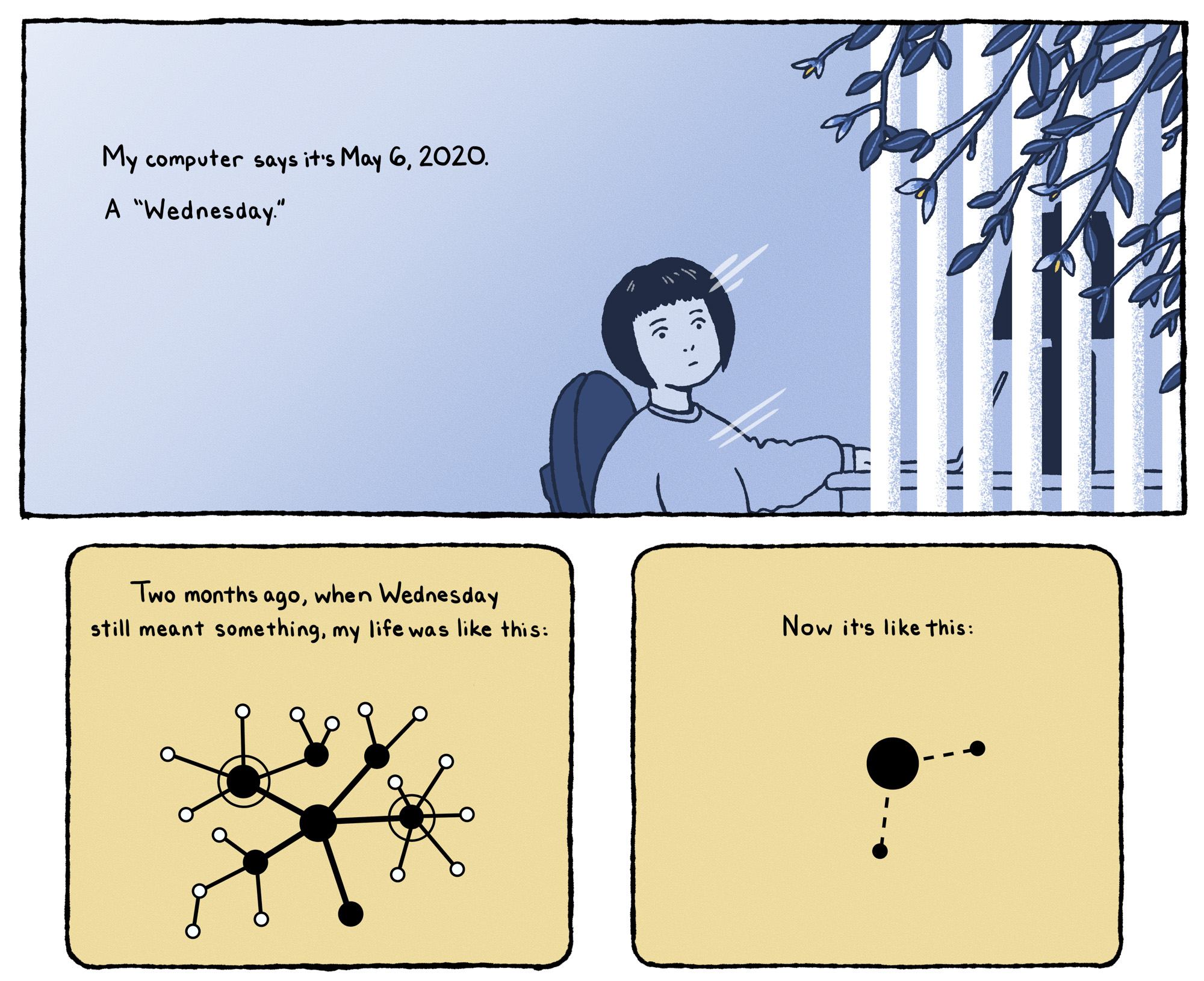

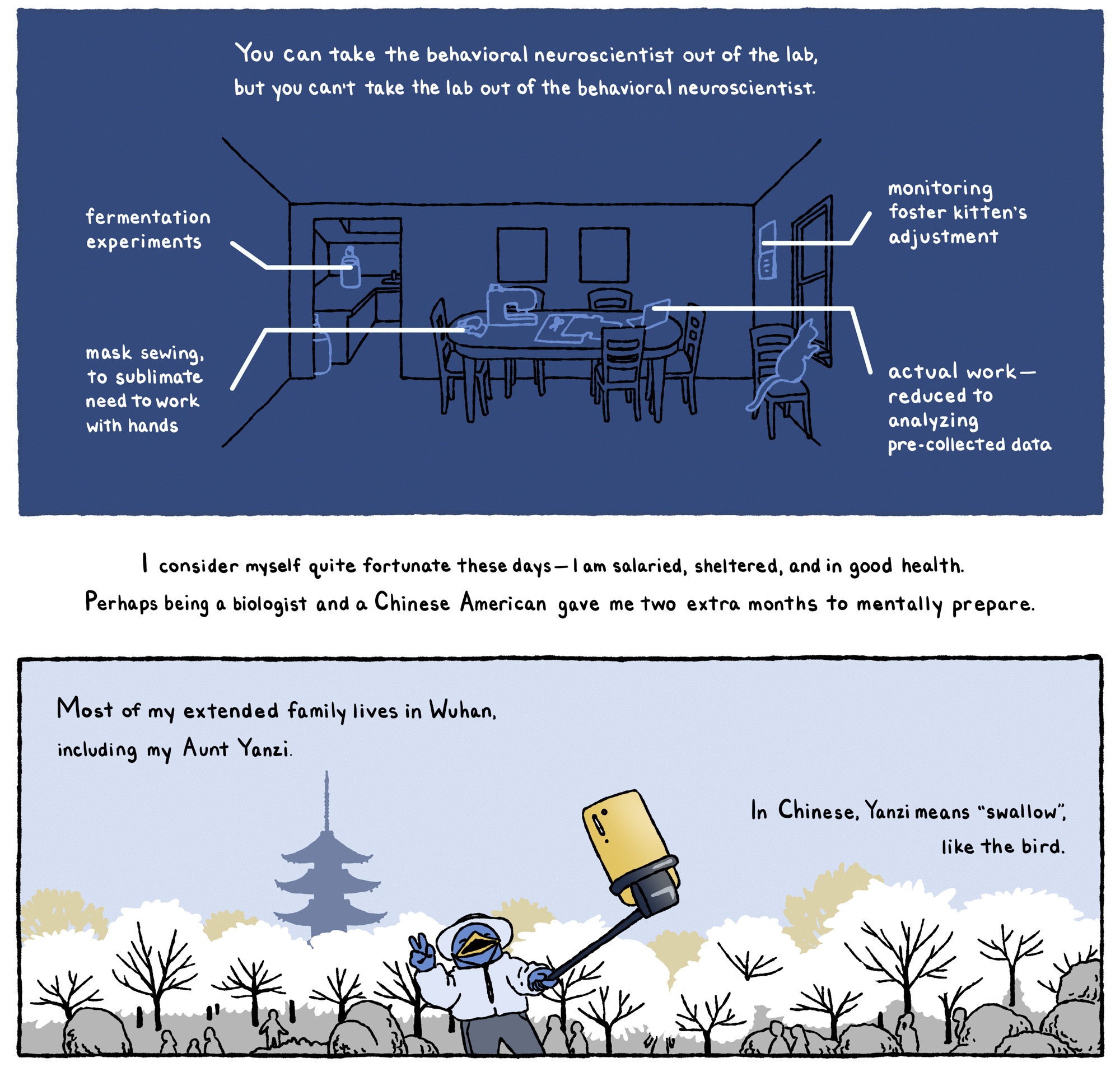

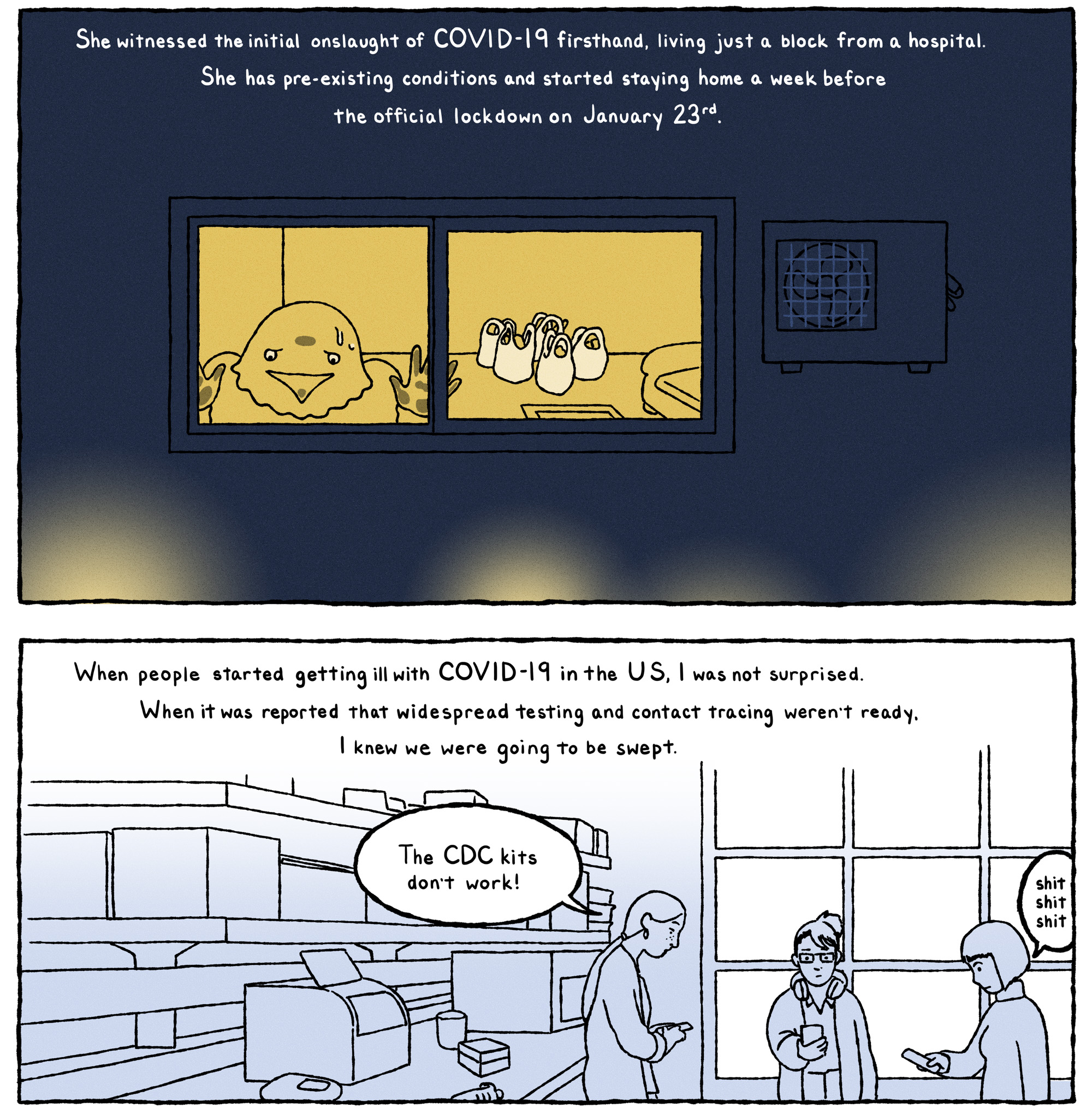

BY CAROLINE HU

The Privilege of Social Distancing

BY SHAWDEE ESHGHI

In late winter, when it became apparent that the coronavirus pandemic would change our daily lives, it felt eerily familiar to me.

In our old home in the Bay Area, we had experienced increasingly destructive wildfire seasons that brought smoky, toxic air from hundreds of miles away to our neighborhood in Oakland each fall. Our kids’ schools were abruptly closed and we had to scramble to be home with them. The half-marathon I trained for was cancelled. We constantly checked the air quality maps and mathematical projections and wondered when it would end. Then, as now, apocalyptical feelings ran high. Then, as now, it was uncomfortable and awkward to wear masks around town, and yet they were our only hope for any sense of normalcy. Then, the threat was visible in the dark daytime skies, ash on our car, and vivid, unnaturally hued sunsets. Just being outside was dangerous, but we took comfort in the company of friends. This time the danger is invisible. This time, other people are the threat.

The wildfires only lasted a few weeks at most. It’s now been over two months that we’ve all been home from our regularly scheduled lives, and it’s clear we won’t be going back to those routines any time soon. For now, my family of four spend our days together: my partner practicing architecture from the corner office formerly known as part of our bedroom, our seven-year-old son half-heartedly rushing through his packet of worksheets to get back to his favorite books, our five-year-old daughter roaming wild from Legos to Playdough to listening to long stretches of her favorite podcasts, and me trying to squeeze my work in synthetic biology into any mental and physical space I can find. We panicked at first, as it seemed impossible to do two full-time jobs and edu-tain two kids without any help. Some countless weeks and Zooms later, it turns out that it actually is impossible. No one can expect parents to continue their pre-COVID productivity long-term without childcare. But as the toll of the disaster increased rapidly, heartbreakingly, around us, it also became clear how much of a privilege our situation is. Those of us who can afford to stay at home and pay all our bills are incredibly lucky. I try to remember this when I feel like I’m failing at everything, behind on work, neglecting my children, feeling guilty about taking a break to go for a run.

The toll extends beyond the easily measured numbers and headlines. And the threat of death doesn’t supplant all banal wishes and concerns. What of my parents, in their first year of hard-earned retirement, who’ve had to cancel all their travel plans? What of my brother, living alone in New York City, fretting about his relationship prospects during a pandemic? And what of my children, missing out on all the growth and development that comes from the routines and socialization of school? Yes, we are the privileged ones, lucky to be alive and working, but these are the people we love most, and their losses hurt too.

Some things are lost, others are gained. With the world largely shut out, our focus on the small things improves. My children have been in full time childcare since they were each 4 months old, and now we get to spend every day together. At our best, we let our curiosity define our homeschool, not the worksheets. We’re eating up all our leftovers. We’ve Zoomed with groups of friends we only see at weddings. We keep close watch on the nest of baby robins in our yard. We’ve started a book exchange with neighbors. We’re driving less. And yes, we’re baking bread. These are the new routines and rhythms of these days and weeks.

As a synthetic biologist, I’ve never felt more strongly about the possibility of science. Since the first SARS-CoV-2 genome was published in January, we’ve witnessed a most dizzying display of the very basic process of science: asking questions, applying the best methods we know, reporting the results, rinse, repeat. I’m hopeful that the collaborative aspect of much of this work will have a lasting impact on the way we as a community approach the problems of the future. While it fills me with rage to see some of our leaders misinterpret (or outright suppress) this work, it’s inspiring to see how much of the public is seriously heeding the recommendations borne out by the data. The novel and fast-paced nature of the virus has forced the public to learn alongside the experts and installed a new level of collective scientific understanding and individual accountability. The pandemic has put the process, power and politicization of science on display unlike ever before, where it is evident to almost every citizen. That feels like progress in and of itself. It’s hard to say when we’ll be on the other side of this, or what that will look like, but despite all that’s lost, there’s so much from this time worth holding onto.

What the Ancient Greeks Taught

BY SUDEEP AGARWALA

Me About Surviving a Pandemic

There are new problems and there are old ones. To people raised in the 21st century, on threats of terrorism, climate change and nuclear conflict, the idea of a plague bringing humanity to its knees seemed a bit anachronistic at first. Pandemics have always had a way of connecting people across distant generations. They allow us to understand our forebears’ struggle with natural forces. They leave behind powerful myths and enduring lessons. Plagues are at the beginning of the Western Canon, starting on the beaches of Asia Minor when Agamemnon captures the daughter of a Trojan priest in the Iliad. They are attested to in the Bible, as Moses and Aaron bring the Egyptian state to its knees. In my own quarantine, I learned how to endure a pandemic by reading the first historical account of a plague, written during a time when the world’s first democracy was in crisis. It remains relevant to this day, not only because of what happened, but because of what happened after.

It is 430 BCE. The Athenian Empire is embroiled in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, when people suddenly start getting sick and dying. Notable Athens’ resident Thucydides, who catches the plague and is one of the few people to survive it, writes about the events of that day for posterity. The disease that sweeps Athens is rumored to have started in Ethiopia. When it first manifests in Athens’s port city, Piraeus, it is presumed to be a plot by the Peloponnesians poisoning the water supplies. But as it creeps into the city it becomes clear that this is something far more serious. Panic and lawlessness sweep through Athens as people fall ill:

[P]eople in good health were all of a sudden attacked by violent heats in the head, and redness and inflammation in the eyes, the inward parts, such as the throat or tongue, becoming bloody and emitting an unnatural and fetid breath. These symptoms were followed by sneezing and hoarseness, after which the pain soon reached the chest, and produced a hard cough. When it fixed in the stomach, it upset it; and discharges of bile of every kind named by physicians ensued, accompanied by very great distress. […]Externally the body was not very hot to the touch, nor pale in its appearance, but reddish, livid, and breaking out into small pustules and ulcers. But internally it burned so that the patient could not bear to have on him clothing or linen even of the lightest description; or indeed to be otherwise than stark naked. […T]he disorder first settled in the head, ran its course from thence through the whole of the body, and even where it did not prove mortal, it still left its mark on the extremities; for it settled in the privy parts, the fingers and the toes, and many escaped with the loss of these, some too with that of their eyes.

We never learn what caused this plague. The closest we come to an explanation are a few lines in Thucydides’ history dedicated to an argument that arises about the language surrounding a decades-old prophecy (had it been limos, “famine”? or loimos, “pestilence”?). Given the state of knowledge at the time, it’s the best he could do. There’s been a lot of work since trying to suss out what happened in Athens in the fifth century BCE. Thucydides’ description of the plague is so detailed that it fueled an entire body of medical literature hypothesizing what afflicted Athens. It’s not the most interesting reading, but I think it points to our current instinct when it comes to disease. One of the greatest achievements of the past 200 years is our ability to pinpoint the cause and effect of infectious diseases. Not only that, but we can shape public behavior around them. It is to science’s great credit that we all know to wash our hands, cough into our elbows, not touch our faces, maintain a social distance of 6 feet, and stay at home if we can.

The possibility of a cure makes it inspirational to be part of Ginkgo right now: rather than stand by and witness the virus spread around the globe, it’s gratifying to be part of the solution — to shape project plans so companies all over the world can innovate new cures and, using our technology, further develop our ability to eradicate disease. The works of nature are formidable; so are the works of mankind. Twenty-five hundred years ago, Thucydides couldn’t address the underlying cause of the plague; we can.

Thucydides isn’t interested in questions he can’t answer. What is interesting to him are the consequences of the Athenian plague, how it affected the city, how it impacted the war and the balance of powers in the Aegean. Time and again we see the citizens of Athens face difficult decisions with no clear answer. Thucydides captures long speeches from opposing sides on equal footing to show how the decisions were made. It’s frustrating to read these speeches and see how the young democracy reacts. Athenians are garrulous and rash — easily swayed by demagogues and, in retrospect, always seem to make the wrong decisions. Thucydides is quick to show us the consequences of the choices of a society in distress.

I suppose this is part of the reason I’ve been returning to Thucydides in the middle of our recent pandemic. On every level, whether on the Senate floor, scrolling through Twitter, hunched over my laptop in a Zoom meeting of more than fifty people, Skyping with family half the globe away, or even staring at my husband in disbelief at the grocery store, the combined volume of our discourse can seem at odds with the decisions that need to be made right now. None of them seem easy or right and there doesn’t seem to be any clear answer until it’s too late to revoke them.

I don’t read Thucydides as a prophet for our current situation. Let’s hope not, at any rate: the outcome of the Peloponnesian War was bleak for Athens. Sparta takes over the Athenian empire; Athens is stripped of its city walls, its fleet, and all of its overseas possessions; democracy is suspended and the city narrowly escapes complete annihilation and enslavement. But the conquered are noble. The Athenians’ method of negotiating these difficult choices is admirable: their openness and candid dialog, as frustrating as it can be to read, must have been infuriating to be involved in and witness. But this messy, uncomfortable conversation also allowed for consent and allegiance to the state and citizenry. The Athenian process and the commitment to the liberties afforded to their peoples is certainly their greatest weakness. But it is also where Athens’ power rested. I read the history of the Peloponnesian War as a tragedy, but Thucydides’ insistence on maintaining the standard of discourse is heroic. Emergencies have a way of exposing the true extent of our principles.