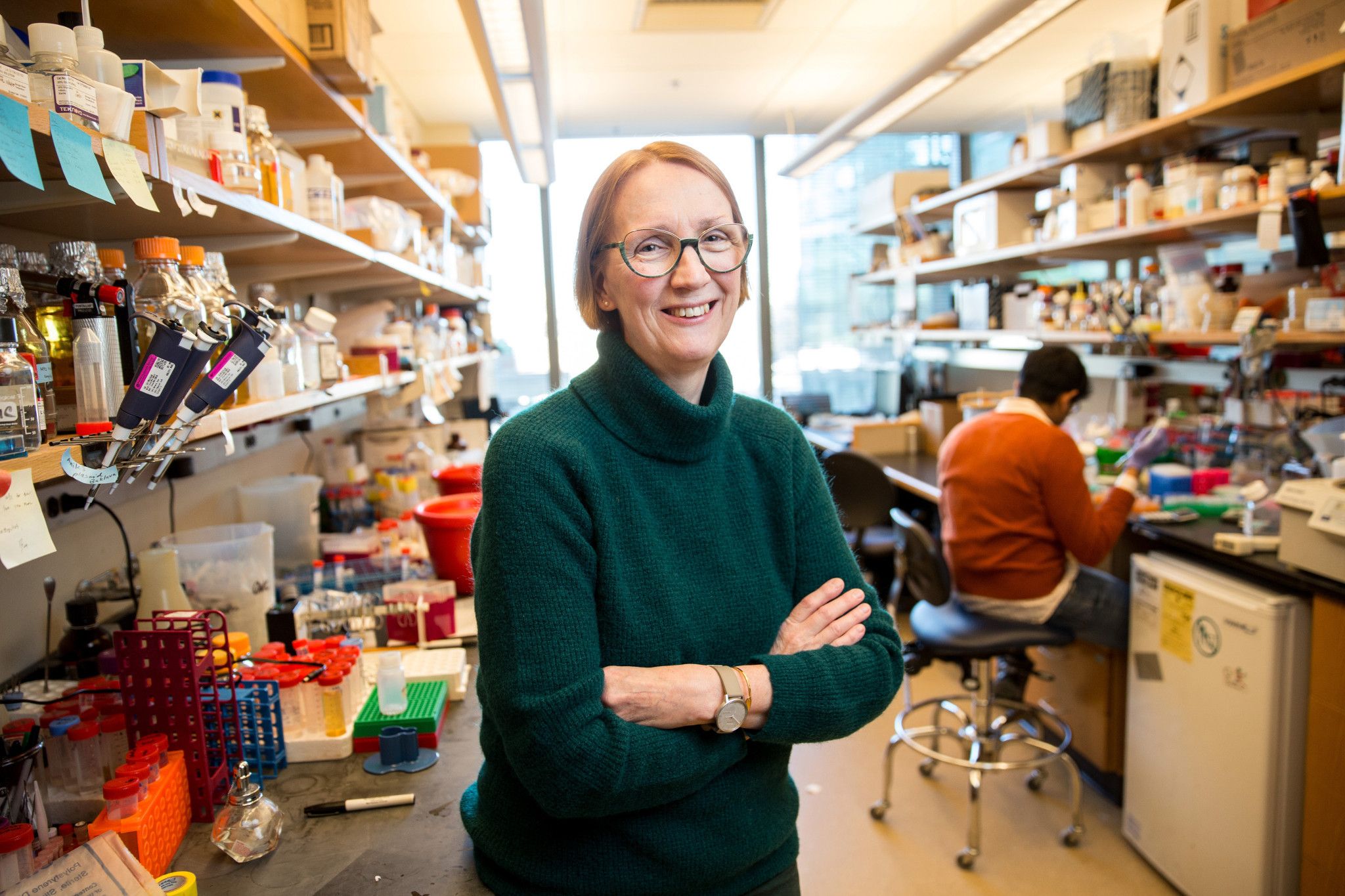

In the second part of our coverage of Xenobots — the world’s first living robots — we speak to Jeantine Lunshof, a philosopher who has been working closely with the research team led by Michael Levin and Josh Bongard to contemplate the implications of their ground-breaking discovery. Her unusual background, between philosophy, bioethics, medicine and science, raises interesting questions. How does a philosopher end up working on the forefront of innovations in bioengineering? What can scientists and philosophers learn from each other, and would the world benefit from more such unorthodox collaborations? Lunshof’s ongoing inquiry into Xenobots offers us a fascinating new vantage point on this radical discovery. These liberated frog cells, sculpted into an entirely new organism, challenge some of our most basic assumptions about nature, biology and cognition. How should we think about this new life form? Grow’s Christina Agapakis sat down with Lunshof to find out.

Christina: Before we get to the Xenobots, I wanted to ask you about your career, which is fascinating. What inspired you to become a philosopher-ethicist, to apply your background in philosophy to a negotiation between the interests of science and medicine, and the rights of regular people?

Jeantine: While I was at university, I became sensitive to the disconnect between academic discourse and the concerns of real people. I was studying Philosophy [in Germany] and working as a cleaner on the side. Some of my fellow cleaners couldn’t read, and I became their go-to person if they, say, received an important letter. I found that these women were experiencing the real ethical questions of our time in a personal and often painful way. Hegel wasn’t any use to me (or them) in that situation.

After spending years of abstracting questions of life and death, I felt the need to ground what I had learned in real experience. I returned home to the Netherlands, went to nursing school, and was immediately put to work in a hospital. That wasn’t easy. After two days on the ward, I fainted watching a patient give blood. Nevertheless, I started working in the pulmonology ward the next day, where I encountered patients suffering late-stage emphysema, people who were about to die from respiratory illnesses or cancer. In three months, I felt I had learned more about the big questions of human existence than I had during the duration of my philosophy studies.

I became an expert in the disconnect between those two worlds. After years of working in a Clinical Research Unit of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, while pursuing my Masters in Philosophy and Health Law, I started working as an ethicist at a Dutch patient and parent organization on behalf of people with genetic disorders. This was another important fault line: between philosophical arguments on medical ethics and the real-world concerns of sick people and their families.

Christina: What you’re saying about philosophers is, I think, also true of scientists. We study these questions of human health and disease, but it’s often very abstracted from the reality of people’s experiences. You’ve been able to bridge these worlds. How can scientists do that, integrate the perspectives and experiences of outsiders into the way that we ask questions?

Jeantine: I feel very strongly about this. When you talk to me about osteosarcoma, for example, I see the patient I had with that and how she died, how little we could do. It will never be an abstraction to me. The key I think is encouraging more exchange between disciplines, which requires both sides acknowledging their limitations. When you talk to philosophers about cancer or genetics, many of them have a very vague sense of how the people they theorize about actually live. Scientists also may not always be aware of how their work is understood. It requires great patience to bridge that disconnect.

It’s also important to realize that there is almost never a single ethically ‘correct’ answer that satisfies all sides. I realized the complexity of this when I conducted a study on attitudes surrounding genetic testing among patient advocacy groups and clinical geneticists in Germany. In the early nineties, molecular diagnostics were just beginning to become part of the debate — a charged debate about prenatal screening, genetic diseases, and abortion. People were protesting outside the Human Genetics Institute, accusing them of waging a eugenic campaign against people with disabilities. On the other hand, I had met enough patients and parents of children who suffered from these disorders to know that they were waiting for these types of diagnostics.

Christina: How do you mediate in that kind of situation?

Jeantine: You ensure a transparent conversation. On both sides, there were people who were very hesitant about molecular diagnostics and others who were hopeful about it. In the middle, there was something approaching a consensus that parents should at least have prenatal testing as an option.

Christina: Today you work as an ethicist and philosopher at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, among scientists and engineers. What interested you, as an ethicist, to start working in that world?

Jeantine: I worked with George Church when he started publishing on the Personal Genome Project (PGP), which aims to sequence people’s genomes and to find links between particular genes and specific health conditions. He was facing a lot of criticism because he had proposed that participants make their genome and their health records publicly available. As an ethicist with my set of experiences, I could see this issue from multiple vantage points. Ethically, it was totally unheard-of, this total relinquishing of confidentiality or anonymity. It posed major challenges to our long-term concepts of privacy, identity, and consent for research. Biologically, however, it is by definition impossible to promise people anonymity while harnessing their genetic material.

I also knew that anonymity wasn’t the top priority for families actually dealing with diseases. Pre-internet, parents with children suffering from developmental disorders would send photos to each other in the mail. ‘This is what our baby looks like. Has anybody seen this?’ So in those communities, exchanging information that could possibly help their child find the right doctor was more important than privacy.

I concluded that we likely needed to change our concepts and rules rather than clinging to the belief that we can confine the genomic sciences to a box designed by the humanities. That work resulted in the ‘open consent’ put into practice since 2006 in the PGP, an entirely new model of consent in which research participants agree to make their data—comprehensive genotype and phenotype data—publicly available in an open access database. The PGP, featuring veracity, reciprocity and altruism, remains the only project where participants give ‘open’ consent for unrestricted use and unknown future use and where they consent to giving up anonymity.

This is important for advanced synthetic biology. Material and data from PGP participants — also available through Coriell — is the only material that can be used with full and valid consent for cutting-edge experiments like in-brain organoid research, animal-human chimera experiments, as well as bio-bot research if they are designed with human cells.

Christina: How did you start working with Michael Levin on the philosophical questions surrounding Xenobots? What did you bring to that conversation?

Jeantine: The focus of my work shifted a number of years ago to the study of conceptual and normative questions surrounding brain organoids and engineered living entities. I learned about Mike’s work in that context and reached out to him, and the resulting collaboration brought my work into new dimensions. Bioengineers like Mike Levin are bringing living entities into being that never could have existed in nature — organisms with recoded genomes, for example. What does that mean, to create life that does not occur in nature? It triggers a philosophical reflection, about biology, about what is natural, and about engineering as human action.

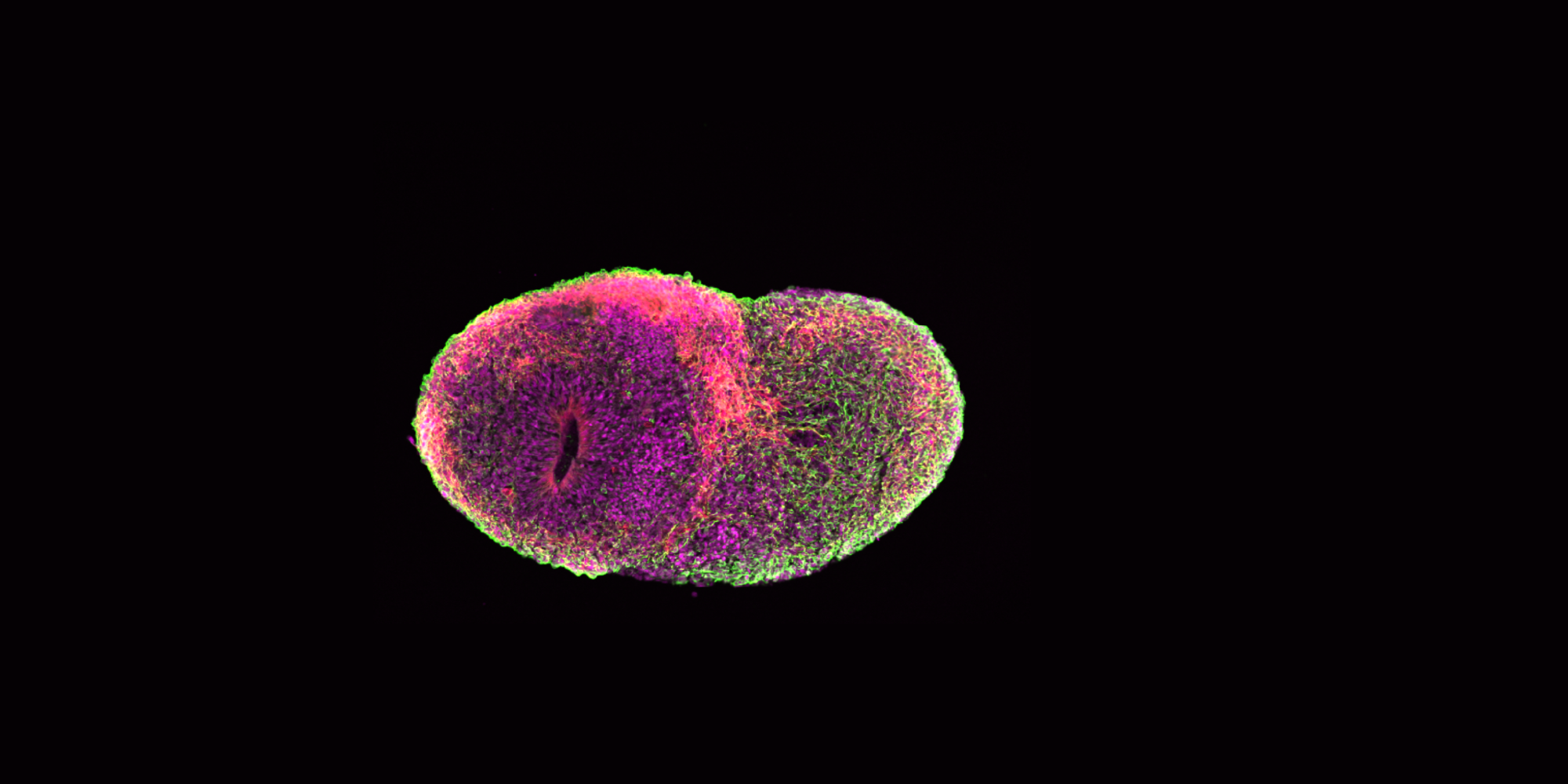

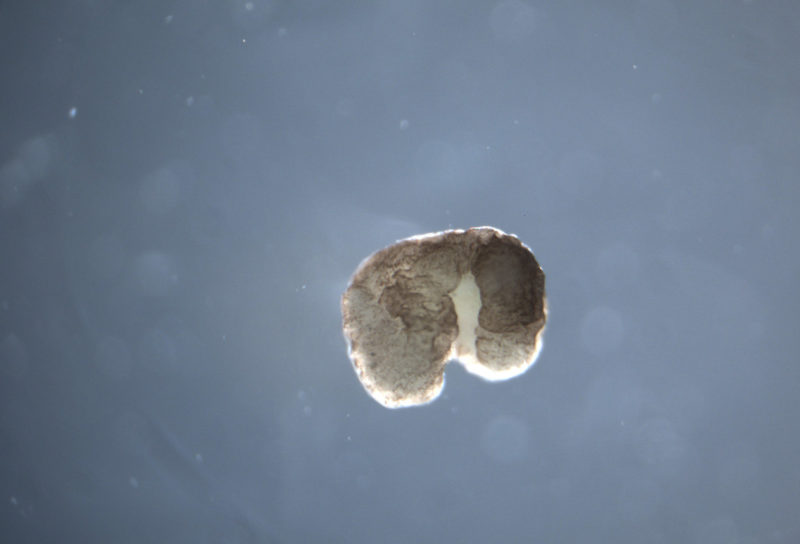

‘Bioinspired’ engineering poses a radical challenge to existing philosophical concepts. Philosophers and ethicists have built their theories of existence without considering the potential existence of, say, synthetic embryo-like structures, or the real possibility of changing the codon number of the genome of an organism. We’re witnessing an expansion of the evolutionary tree. Xenobots are the ultimate frontier, in that respect. They could never ever occur in nature.

Christina: In addition to the consequences and ethical frameworks for new technologies, your work also engages with the conceptual language and metaphors that scientists use to make sense of things. What struck you about the way Michael and his team describe Xenobots?

Jeantine: The language and terminology is puzzling at first. As you can see in Mike’s Q&A, he uses words that come from what I might call our anthropocentric world. He describes processes in biology as ‘actions,’ including ‘actions’ by what we regard as ‘simple organisms,’ such as bacteria. He uses the language of “decision-making.” These organisms have goal-directed behavior, but goal-directedness is a feature of any living system. He describes the ‘actions’ of these organisms in terms of ‘basal cognition.’ This is setting us up for a great confusion that demands philosophical unpacking.

Our language — the sense and reference or, more colloquially, the meaning of words — is the vehicle with which we travel from the anthropocentric world into the biological world and back. For us, in the anthropocentric world, decision-making involves a decision-maker, an actor, an agent. Agents have ‘agency,’ a key notion in concepts of autonomy and at the very core of ethics. How do we differentiate between ‘agency’ in biology and the agency of higher organisms, such as humans?

It has been fascinating to learn from developmental biologists that they regard basal cognition as essentially the same cognition we see in higher organisms, all the way up to humans. This is a great example of how biology challenges philosophy, as we now need to address the question of the difference between a-neural and neural cognition. So far, we have only been using ‘cognition’ to describe organisms with neural systems, and commonly only for higher organisms with central nervous systems. Many ethical inquiries start from the assumption that certain characteristics are specifically or even exclusively human; to what organisms, aside from humans, do we ascribe cognition? Cognition is not identical with consciousness.

Christina: Has Michael’s research on these questions also influenced your research?

Jeantine: Yes, particularly his earlier work on memory and how it persists over state transition. For example, his research group discovered that when a caterpillar morphs into a butterfly this remodels their central nervous system. That’s mind-blowing! These observations of the brain of a non-human animal pose a critical challenge to our understanding of the human brain and our human memories. It connects with my work on the philosophical and ethical questions in brain organoid research, a collaborative project of philosopher-ethicists (Insoo Hyun and myself), neuroscientists, and others.

In philosophy and ethics, the question of what the brain actually is and what it contains, how it works, and whether there can be anything like memory or consciousness in these organoid models (self-organizing, stem-cell derived neural cells, and tissues used as 3-D models of the human brain) is a topic of hot debate. Do our observations of memory retention over metamorphosis change our idea of what memories actually are? Do memories have any material substrate? Are they chemical, or are they maybe bioelectrical? This confronts you with unanswered questions about the philosophy of mind, questions persisting over millennia. One of the key questions is known as the ‘mind-body problem’, asking whether the ‘mind’ exists independent of ‘matter,’ the brain.

In my experience, scientists are thinking a lot about these questions. I encounter many who have taken philosophy courses as part of their studies. In some new areas, in the neurosciences, or in research with brain organoids, the philosophical questions are in plain sight: what are we engineering when we model the brain? The ontological (what is it?) and epistemological (how can we know it?) questions precede the ethical ones. This is what scientists discuss, even if they use different words, and this makes them fascinating conversation partners for a philosopher.

Christina: How do you conceptualize these Xenobots? What are they even?

Jeantine: The cells are derived from animals. Does that make a Xenobot an animal? I don’t think so. There is even the question of whether they are organisms, at all. They are certainly a life form. If one takes the ability to reproduce as a criterion for ‘organisms,’ Xenobots are not organisms — yet. They could obtain that ability, however, if we bestow that upon them. Taking that step, engineering reproductive capabilities in Xenobots and similar constructs, will require extensive multidisciplinary deliberation. Questions will arise somewhat similar to those with gene drives.

Xenobots are the products of computational design, engineered as an assembly of living cells, which means that, while the lifeform is made in the lab, the life itself is not. Xenobots are described as ‘agents.’ They can do the things they have been designed for and likely more. That raises the question of the agency of the Xenobots, and on the other hand the agency, intentions, and responsibility of the engineers. The goal-directed behavior of Xenobots has been designed to meet the purposes of the designers. Could they evolve to go beyond that?

Christina: Did you find yourself having specific ethical concerns?

Jeantine: As of now, I do not regard Xenobots as morally considerable entities, in the sense of a being that can be wronged. The animals from whom the materials have been derived may have a certain degree of moral considerability. In the traditional anthropocentric view, moral considerability is attributed to humans specifically, but the moral status of animals, that is, whether they have interests of their own and can be wronged, has obviously long been a matter of debate. One line of argument is that the closer a sentient being is evolutionarily to humans, the stronger the case is for conferring moral status. This is not only a pressing issue in animal ethics — where the criterium of sentience can be used — but also increasingly in environmental ethics: biotopes, landscapes, oceans. The planet can be ‘wronged,’ so shouldn’t these aspects of it be deemed morally considerable? Finding a place in the landscape of moral considerability for human-engineered living entities, whether or not they contain human cells, is the next big challenge for philosophy and ethics. Relevant ethical questions may arise concerning the purposes for which the Xenobots are designed and used. The question is whether living engineered entities differ in any ethically significant way from other non-living products of engineering.

Christina: How should I imagine your discussions with the scientists?

Jeantine: They come to my desk and say, “Hey, do you have a moment? Do you think this would be weird?” or “What does this mean?” “Is this acceptable?” “What do you think? Am I crossing a line there?”

Christina: In a way, it seems like your presence in the lab gives space for those kinds of ethical questions, makes them more acceptable, because those questions don’t usually end up in the scientific research articles. How can the questions you’re opening up and making space for be more accepted as part of the process of scientific discovery and communication?

Jeantine: I believe the sciences are changing our philosophical and ethical arguments, and not so much the other way around. People hear that I’m an ethicist and think that I will walk up to them and say, “How about we draw some ethical boundaries here?” No, it’s more like, “Wait. This is going on. Should we reconsider our point of view?” Being in the lab puts me on even keel with the scientists, because we’re learning together. They are also seeing many of these research findings for the first time. This enriches my discipline — it contributes to philosophy and to ethics, to our body of knowledge and how we view things. I call it “Bioinspired Humanities.”

Christina: So much scientific work intersects with these really big philosophical questions, questions about humanity and our social existence, and even if scientists as individuals are quite thoughtful about these questions, we don’t always have the tools to really ask and answer those questions the way a philosopher does. That’s something that has shaped my career: seeking out people like you to be able to have these conversations with. Should every scientist have the opportunity to have a resident philosopher or ethicist in the department asking questions with them? How can these questions be part of the way we practice science?

Jeantine: I’m not sure every lab needs an ethicist. That would be overkill and may lead to a hyper-inflation of ethics. In most labs, you may not have enough issues to keep someone busy all the time. On the other hand, in the Wyss Institute, or in the Department of Genetics, for example, they could easily keep three full-time philosopher ethicists busy, because they are dealing with fundamental questions about life, the human genome, and also human identity and ancestry, which have direct impact on people’s rights. Who owns people’s DNA? Who has the right to research what? These are profound questions that need to be asked. It’s my job to ask them, and I’m not shy about it.

Unfortunately, we are still at the point where the sheer novelty of a philosopher working in a lab — or joining a science department — comes up against all kinds of administrative barriers. While the humanities’ contributions are much-welcomed, there isn’t any funding allocated to it. The obstacles to integrating science and the humanities — which would make science more ethical, and the humanities more useful — are purely economic and organizational, and have nothing to do with the scientists themselves, who are overwhelmingly interested in and committed to these exchanges. I suppose this is better than the other way around: budgets can be changed, but acceptance and trust are hard-earned.