When COVID-19 began its deadly sweep, no one — including heads of government and their leading scientists — fully understood how the new virus worked. Those early days of panic were filled with mixed messages from the expert class on everything from modes of transmission to masking. The one thing they all seemed to agree on was that we should quarantine. Quar, as we now call it almost affectionately, was designed specifically for this situation of uncertainty: when you have no way of knowing who’s sick.

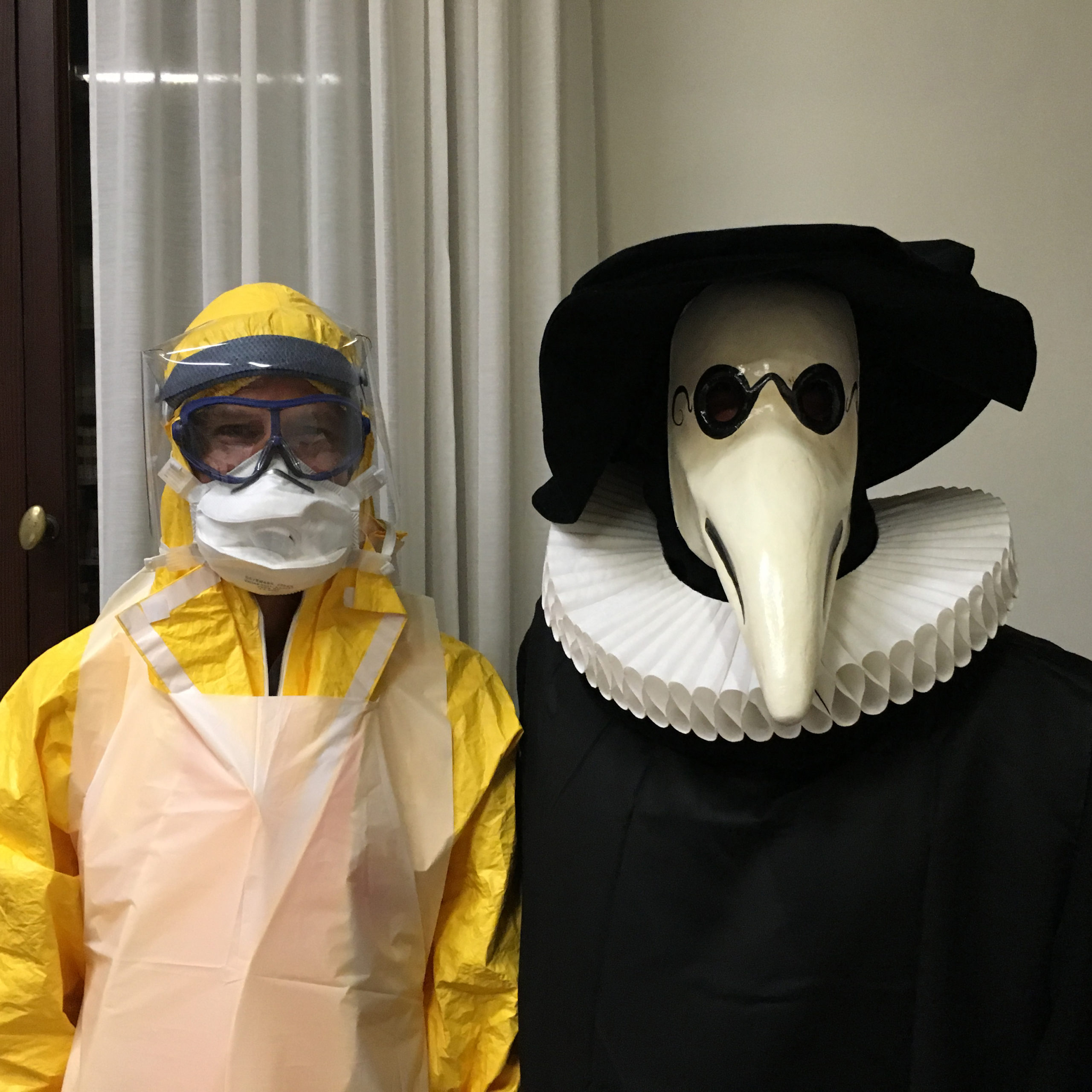

Intellectually, at least, Nicola Twilley and Geoff Manaugh were freakishly well-prepared for this new world, as they had long been researching a book on quarantine. By the time COVID-19 hit, they had been traveling around the world for years, researching the practice that can be traced back to the 14th century. With all this history in mind, the writing couple experienced the pandemic — its evolving hysterias, rules and regulations — in waves of uncanny historical echoes. Initially intended as a warning for a future pandemic, their book became an explanation for what was happening all around us. Their upcoming Until Proven Safe: The History and Future of Quarantine is invaluable reading for anyone trying to demystify this ostensibly novel situation that defined the past year of our lives.

I was lucky enough to sit down with Twilley (New Yorker science writer and host of Gastropod) and Manaugh (acclaimed architecture author) and ask them more about the history of quarantine — what it tells us about our fraught relationship with science, the recent outbreaks of xenophobia, and the future of crisis architecture.

C. Kaye Rawlings: You two had a particularly eerie experience of COVID, in that you were already hard at work on a book about quarantine when the pandemic hit. What attracted you so precociously to this subject, and how did you adjust your approach in response to this worst-case scenario?

Geoff Manaugh: We first took an interest in quarantine during a trip to Sydney, Australia, about 12 years ago. We noticed an old quarantine station that had been turned into a kind of spa hotel. We started to realize that a lot of the places that we’d seen and visited all over the world were, at one point, built and dedicated to quarantine. So, the initial interest was trying to figure out: What is quarantine? What happened to it? Why is it leaving these fossils and ruins everywhere?

Nicola Twilley: We were in a bit of shock when COVID happened, because the working title of our book [at that point] was “The Coming Quarantine.” The argument we wanted to make was that we’re not ready for a future pandemic, that we’ve done it wrong in the past, and wondered how we could do it better next time. When COVID hit — and suddenly half of humanity was under some form of lockdown — we initially panicked a little, because everything was happening so quickly and we were finishing writing our book. Luckily, we had done a lot of travel and research before lockdown, which was very fortunate because we couldn’t have done it after. What became interesting was watching the same arguments play out again, the same issues that we had seen in past quarantines. In 14th century Dubrovnik, for example, where quarantine was invented [during the “Black Death”], they had their own debates about essential workers. Also, seeing the ways that people of Asian origin were demonized during COVID-19 — that’s a consistent feature of the uncertainty and suspicion built into quarantine. It was anxiety-provoking, and then sort of astonishing, when we would find ourselves writing a chapter about history and it mirrored what was happening in the news.

C. Kaye: You open your book by making what strikes me as a really important distinction, between the often confused and conflated practices of “quarantine” and “isolation.” Can you briefly lay out the differences between these two practices and why it’s important that readers understand the distinction?

Geoff: In simple terms, when you’re isolated it’s because you’re known to be sick. You’re not in quarantine, in that case — you’ve been isolated. Quarantine thrives on uncertainty. You quarantine when you have been exposed to something but we don’t know if you actually have the disease. Quarantine is built around interesting metaphoric states, where there may or may not be something infectious inside of you waiting to break free. That really touches on medical symptomatology, but it also foregrounds the religiosity of quarantine. The fact that, historically, quarantine is 40 days long is conceptually tied to the numbers’ biblical significance.

Nicola: Even some medical professionals use these terms interchangeably. Many people are not aware that there is a difference at all. The reason we wrote a book about quarantine rather than about isolation is because it’s a gray area. It’s the complete inversion of this idea of innocent until proven guilty. In quarantine, you are dangerous until proven safe.

C. Kaye: In your book, you write: “We realized that, by examining what, where, and why we quarantine, we were not only exploring the limits of scientific understanding, but also excavating our deepest fears, biases, and sense of identity. Quarantine reveals how we define and police the perimeters of self and other, as well as what we value enough to protect — and what we are willing to sacrifice.” What have you learned about yourselves, and your relationship to this community of others, while writing about and then experiencing quarantine?

Nicola: What really struck me was how weird the quarantine experience was for European travelers who were used to thinking of themselves as the “not dangerous ones,” “the clean,” “healthy,” “safe” ones, as opposed to the rest of the world. During COVID, seeing people put their mask on around me was this reminder that they saw me as potentially infected and indeed I could be. One thing that was so strange about COVID-19, and hard for people to compute, was that you could be a source of danger unknown even to yourself. That’s a very hard kind of thing to reconcile with your self-image. It’s very unsettling to think of yourself as a potential danger.

It is interesting to think about how moral virtue is performed in such a situation. Initially, quarantine was framed as this communal experience — a way for people to fight something invisible, deadly, and terrifying together. And this is a key part of quarantine’s history. During some outbreaks of the plague, one in three people would die; there was a very real risk of total social breakdown. This idea that we would visibly demonstrate that we’re all doing the right thing together, protecting ourselves, and fighting against something invisible together has historically been immensely important. You can see echoes of that in masking today — people who are vaccinated are still wearing masks, people walking alone wear masks. That’s a visible sign that says, “I am fighting this with you.” It is part of that wish to show that they’re part of a larger civic society that is trying to fight this together.

Science isn’t good at communicating uncertainty.

NICOLA TWILLEY

C. Kaye: Covid-19 has been this rare communal scientific experience — where almost every member of society was pressed to take a stance on a scientific question, with all kinds of implications for their lifestyle, their politics, not to mention their survival. How has the pandemic, and the government response to it, informed the public’s relation to science? More to the point: do you think that the reason so many Americans understood the stay-at-home or mask mandates as this political overreach was due to a lack of government action or a failure of the state to straightforwardly communicate public health messaging?

Geoff: I think confused messaging was definitely part of that. Even the Surgeon General was tweeting — in March 2020 — something like ‘seriously, people, stop buying masks! They won’t protect you from COVID.’ The World Health Organization at one point was saying that they didn’t see any evidence of human-to-human transmission in China. The greater problem over here, meanwhile, was that there wasn’t a clear federal response to COVID. Instead it was kind of up to you whether you were responsible, whether or not you remained healthy, whether or not you did what’s best for your family. The lack of government intervention put too much responsibility in the hands of individuals.

Nicola: Even beyond the specific political circumstances in the US, which were terrible, quarantine is a tricky, slippery, and risky topic because it’s based on uncertainty. I think there’s something to learn here about how science isn’t good at communicating uncertainty. People would much rather have a definitive answer and be able to stop worrying. Quarantine, almost by definition, requires you to worry about it.

Geoff: Historically, quarantine was a sign of rationality and even modernity in terms of how it approached the idea of infection: separating people and things from each other and then to wait and see what happens. The whole thing was a very rational approach to using space for a proto-scientific experiment. The ironic thing is that today quarantine can almost seem like superstition. When we couldn’t confirm how people got COVID, telling them to stay in different rooms for now, or to try these different things out, made medical professionals sound like they didn’t know what they were talking about.

C. Kaye: In the book, you point out that early quarantine facilities show us that people in the 14th century already had a robust understanding of infection well before the advent of germ theory. Can you describe these facilities, how they developed, and how they reflect the proto-scientific ideas of the time?

Geoff: I guess you could say that the logic of it began more geographically than architecturally. There was the realization that when goods or crews arrived from certain places it coincided with the outbreak of a disease in the host city. In Dubrovnik or Venice, people concluded that there might be something else on that ship or something else in those goods that explained why disease spread after its arrival. The next step is to see what happens if we delay the arrival of a ship from that location and see if the disease still pops up. In looking for a place to delay those arrivals, that’s where you start finding the early geography of quarantine. If there is a city with an island nearby, they’ll go put the newcomers on that island, or if there’s a bay nearby, they will anchor the ship in that bay, and so on. Over time this geographic practice took architectural form. They created little islands with architecture. So you would have a particular ward for a ship of people and then within that ward, there are separate rooms for individual people, and then there are courtyards outside for the goods. Visually, they are often beautiful buildings. They’re very much like old fortresses or castles, because that’s basically what they are, you know, they are “fortresses of health” and “castles against an invisible foe.” Very thick, heavy masonry.

C. Kaye: You write extensively on how fear of disease has often translated into fear of the other. You cite, for instance, the 19th century typhoid epidemic, where quarantine policies unequally affected Irish, Russian Jews and other Eastern Europeans. How do you square this history with our most recent COVID epidemic, which has unequally affected poor black and brown Americans, not because they were asked to quarantine — like in the 19th century — but, as it turns out, because they were being asked to not quarantine?

Nicola: I think the issue around the ability to quarantine and having the resources to keep yourself safe in quarantine is also something that we can trace back in history to places like the Lazarettos in Venice. The Lazarettos were considered a public good; they were one of the five institutions in a city that people left money to in their wills. The idea was that poor people would be housed there — that they would be provided the resources they needed to isolate. That’s something that we did not see much of during COVID. We spend a lot of time in the book talking about this. The people currently responsible for implementing quarantine at the federal level, for example Marty Cetron who runs the division of global migration and quarantine at the CDC, were very aware that you couldn’t ask people to quarantine without providing support. But those kinds of precautions are only built into federal quarantine policies, not necessarily at the state level.

We should anticipate multiple uses for buildings during the design process, so that when events like this happen, it’s much easier, and much cheaper, to effectively transform them.

GEOFF MANAUGH

C. Kaye: And it didn’t have to be this way. You give a powerful example of how China used quarantine facilities to help build and sustain communities called “fangcang.” They converted huge public venues into temporary hospitals, where they isolated patients with mild to moderate symptoms from their families and communities, providing them medical care, disease monitoring, food, shelter, and social activities. They not only helped “slow the spread” more efficiently than in the U.S., but that also eased the psychological distress caused by quarantine. Why did that work in China and not here?

Geoff: The lightning speed construction of these facilities in China really helped. It really comes down to the will to do it. In the U.S., the Army Corps of Engineers would be just as capable of erecting a super hospital in a very limited amount of time, but they never got the order to do so.

Nicola: The U.S. military actually went ahead and used essentially the Chinese model for their own — for military personnel. When military personnel had to travel somewhere they all quarantined in a sort of decentralized way. It was set up very much like in Hong Kong. But that wasn’t done with U.S. civilians. Erin Westgate, a researcher who studies boredom, suggests that we lacked the right incentive structures to make this sort of “communist” quarantine palatable to people here. Americans really prize their independence and the idea that they are free to do whatever they want to do, so you have to provide people choices to either quarantine in this centralized way or do it at home.

I do think there’s something really important about stressing the idea that quarantine is something that we are doing for the public good. And yet, because you are distancing yourself from other people, it’s very alienating. The fangcang in Hong Kong were an attempt at addressing this alienation, so you could reap the emotional rewards of the public-spirited gesture that you’re making. That spirit was lacking in the U.S. and much of the rest of the world.

C. Kaye: The Army Corps of Engineers did do a lot of building during COVID. Could you talk us through some examples of what the Corps did, especially what were called “small room” and “big room” conversions?

Geoff: I think what’s so interesting about what the Army Corps of Engineers did was that they were presented with a pretty daunting architectural challenge, which was to come up with a solution for housing, separating, and isolating potentially tens of thousands of people that had been exposed to COVID. And they had a really clever response. They came up with this plan to help convert already existing and, at the time, unused architectural structures and give them a useful double life as part of the nation’s frontline medical infrastructure. The idea was that you could take an existing motel — or maybe a dorm room, or an entire dormitory, you could even look at things like sports stadiums, convention centers — and convert them for medical isolation. And this idea has a history. Back in 2009 we interviewed the head of the American Public Health Association, and he pointed out how dual-use infrastructure is something that effectively every nation should have. We should anticipate multiple uses for buildings when we’re first designing those structures to begin with, so that when events like this happen, it’s much easier, and much cheaper, to effectively transform a building.

Nicola: While “big room” conversions are of stadiums, sports arenas and convention centers, “small room” conversions are where you take the Marriotts, or the Fairfield Inns, and you flip them. What I thought was so fascinating was this idea that across America there are all these identical rooms. I mean, if you’ve seen one Springfield Inn and Suites you’ve seen them all, you know? And that became an asset. It might seem like a bummer that all of America kind of looks the same, but for the Army Corps of Engineers it meant that you could use one method to turn every Marriott into a hospital for COVID isolation patients. As it turns out, America is already a template. The Army Corps of Engineers could lay out “these eight things” that you needed to do to suddenly create thousands and thousands of new hospital rooms. It’s a silver lining of America’s otherwise monotonous architectural landscape.

Well, they didn’t end up being used, not as much as you would think. What Todd Semonite [then 54th chief of engineers, Lieutenant General] told us was that there was an economic incentive not to send folks to these hospital conversions. They [private hospitals] make more money when the person is in a hospital — even an overcrowded hospital where they had to crowd people in a room or in corridors. That’s an example of where America’s privatized health care created counterproductive incentive structures.

You can’t have public health without a public.

Nicola Twilley

C. Kaye: Could you give us a sense of how quarantine and infectious disease containment has changed in the U.S. since the midcentury and then, again, in the 1980s, as outpatient care became more commonplace?

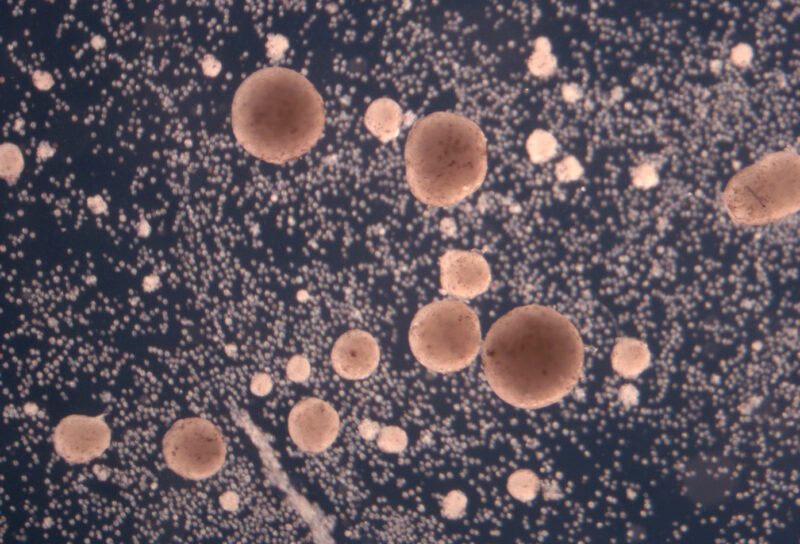

Nicola: Some of this has to do with the fact that in the 1950s, people started to believe that the war against infectious diseases had been won and so there was no need for facilities capable of isolating or quarantining people. And then the other piece of the picture is that the business of healthcare changed. There was a deinstitutionalization movement. The old institutions that existed to provide care to, say, people with Hansen’s disease (leprosy) were closed. People returned to their homes and got care at outpatient clinics. There were no longer facilities for isolation or quarantine. In our book, we talk to Ted Cieslak, who runs the National Quarantine Unit in Omaha, Nebraska. Prior to that, he ran something called “the slammer,” which for a while was the only sort of high level containment unit that existed in the U.S. People like him argued for these kinds of facilities and knew that if a highly infectious disease came along we were going to be screwed.

Geoff: The politics of isolation and quarantine have also changed pretty dramatically since the 1950s. In the 80s, during the AIDS epidemic, people were trying to rewrite quarantine laws to be less invasive and, at the same time, you saw an authoritarian use of quarantine powers, like in Guantanamo Bay where then Attorney General William Barr used quarantine powers to house Haitian refugees.

Nicola: AIDS was one of the first new infectious diseases with pandemic potential and absolutely no cure or treatment. And what was also interesting about it is suddenly people said, well, we’ll use these tools that we have for handling legal medical detentions for isolations and quarantines, but the laws surrounding them hadn’t been updated since the 1918 flu. The laws were not at all compatible with the advances that had been made in guaranteeing individual rights under the Constitution. There was this belief that quarantine was unworkable under contemporary ideas about human rights; that our conception of individual rights had made quarantine impossible, and untenable.

C. Kaye: Speaking of these conversions, in your book you mention how, historically, quarantine facilities are rarely permanent. Could you speak about this liminal space between the permanent and the temporary that we saw develop during COVID? Going forward, how do imagine these spaces, that don’t necessarily need to be occupied at all times, will be treated?

Geoff: I do hope that this time kickstarts a new imaginative relationship with these spaces, so that they can be more easily transformed and used again. That’s just a kind of a win-win situation for everybody, including landlords that need an alternative use for a building that’s been emptied out, either for economic reasons or for pandemic reasons. But, honestly, I’m not optimistic that this will happen. I don’t think that the United States, either politically or economically, has the will. I think it’s possible that, on a small scale, you might find a particular university or hotel chain that might make some minor changes, which would allow the structure to be flipped over in an emergency. It will be really, really interesting to track this in the years to come and see how (or if) the temporary becomes permanent.

C. Kaye: Your book made me think about these large-scale federally-subsidized vaccine sites that FEMA is running across the country. If you had room in the book, how would you have treated or historicized these massive vaccine distribution practices? Why would you say that the vaccine rollout has been so much more efficient and effective than COVID prevention and treatment in the US? Where was this organization and political will in preventing the spread of COVID?

Geoff: Well, one of the reasons why mass vaccination has been more successful is that it doesn’t require really anything on behalf of the American individual except to show up and get a shot. And I think that anything that requires an imposition on an American to change behavior — even if it’s as simple as putting more air in your car tires, because it might help fight climate change with fuel efficiency — is considered a bridge too far.

The other thing we’re just seeing culturally — and this is a much larger question, in my opinion — is a growing divide between civilians and the military in the United States. When American civilians see how efficient the military is run, and can get tasks done, they are justifiably impressed. The military can fly to a completely foreign location and build an instant city in practically a month, complete with services and restaurants and whatnot. Leaving aside the geopolitical implications, that shows how quickly things can get done. When people in fatigues are all-of-a-sudden giving three shots every two minutes to thousands of people, it’s a nice realization that Americans can get the job done when we put our minds to it.

Nicola: The reason the military can do that is that the military is funded to do that. That’s why Cal State looks so impressive. It’s the money. The other thing I would say is that — while the vaccine rollout has been amazing and the science has been incredible — wherever there are inequalities during an emergency you’re going to fail. That’s why the communities that are not getting vaccinated are the same ones where the variants are emerging. These are the communities that we should have been reaching during COVID. It’s like we say in our book: you can’t have public health without a public.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.