When Liz Parrish walked on stage at the Longevity World Forum in Valencia, Spain, late last year, the mood in the room palpably darkened. The other presenters knew that the BioViva CEO was about to steal the show again, for better or worse. Where they — mostly starchy academics — had set out modest ambitions to lower the burden of age-related diseases, like heart disease, osteoarthritis, and Alzheimer’s, the avowedly stylish Parrish delivered a more ambitious pitch. BioViva’s goal, she told the audience, was to create a vaccine against aging itself.

Parrish — who is 49 but presents at least a decade younger — claims to be patient zero in her own experiment, a move that isn’t always considered a hallmark of scientific rigor. Amid muttering from the audience, she recounted how she visited an unnamed clinic in Colombia for an experimental gene therapy to lengthen her telomeres, the genetic caps that limit the lifespan of a cell, and another to restore muscle tissue. In the process, she claimed, she had wound back her biological age. And in the next few months, her company would offer this anti-aging gene therapy to the public.

The BioViva CEO may be controversial, but she is not alone. Companies all over the world are proclaiming the imminent anti-aging revolution. If you believe their most enthusiastic research projections, we are on the brink of mounting our greatest challenge to mortality. But how scientifically realistic are these efforts? And are they even desirable? What would it mean for our society if we could cure aging as we know it?

Of Mice and Men

To answer any of these questions, you must start with a more general one: what is aging? It’s not as straightforward as it sounds. “There’s no consensus on what aging actually is,” says James Clement, founder of the independent longevity research laboratory Better Humans. “There are only descriptive definitions.” Chief among these is that aging is the gradual loss of biological integrity — an opaque way of saying that as you get older, things fall apart. Your eyesight fails. Your bones become brittle. Your joints inflame and your arteries harden. You begin to forget.

To regular people, these internal changes are heralded by the outward signs of aging: greying hair, wrinkling faces, progressively sagging skin. Those who manage to elude (or cover up) these changes are said to be “aging well.” Despite its inevitability, our society struggles to make peace with growing old. Though we try to create a more generous language around aging, our fear of it still overwhelms — the anxious sense that youth implies beauty, potency, power, and that this slowly vanishes with the years until we’re old, decrepit, lame.

To slow the transition, we collectively spend some $500 billion every year on tinctures, tonics, tucks, and treatments. Then we grow old anyway. And so, the anti-aging industry draws on a great well of public hope. Their slogans haven’t changed much since the days of the fountain of youth — what if aging is just like any other disease, a condition that can be cured? — but the technology has come a long way.

Curious about all this, I waded through the ankle-deep carpet of an exclusive hotel in the 1st arrondissement of Paris a while back, the guest of Nathaniel David, founder of Unity, a biotech company working on age-related diseases. Over escargots and foie gras, David swiped through photos on his phone showing mice treated with his company’s experimental drug. A mouse lives two years, more or less, and ages like we do: hair falling out, eyes turning blind. It becomes arthritic and moves around less. But David’s 2-year-old mice were sleek, bright-eyed, active, seemingly kept youthful by his medication. Human trials had yet to begin, but investors judged the company to be worth $700 million.

One biotech CEO told me, quietly, that he felt there was “a single digit chance” that he would still be alive in 500 years.

In Silicon Valley, where 35 is considered over the hill, anti-aging startups are a hot ticket. “The great thematic investments of our time are climate change, clean meat, and longevity,” says Jim Mellon, chairman of Juvenescence, a biopharma development company that has raised over $180m for promising longevity startups in the past three years. “There’s no doubt: the theme attracts money. To rich people, the idea of living longer is very appealing!”

Juvenescence’s haul is dwarfed by the two billion dollars of funding ploughed into Google’s secretive Calico (a contraction of “California Life Company”), which seeks to identify treatments “that enable people to lead longer and healthier lives.” Meanwhile, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and PayPal’s Peter Thiel have poured their wealth into companies investigating gene therapy and drug discovery — including Unity Biotechnologies.

“Within 10 years we’ll see stuff that works, glimmers of hope in extending lifespan,” says Mellon. “We’re living at a point where science is catching up with the aspirations.”

And what great aspirations! One biotech CEO told me, quietly, that he felt there was “a single digit chance” that he would still be alive in 500 years.

A Global Greying

Tackling aging is not just an obsession for millionaires and billionaires, but also their friends in government. Health campaigners are sounding the alarm: the proportion at which we’re aging will soon amount to a global crisis. The world’s population of over-60s has doubled since 1980 to around a billion and is expected to double again by 2050. An ever-greater proportion of us are old, and that is bad news for public health. Older people are more likely to suffer chronic illnesses such as diabetes, cancer, frailty, and cataracts, putting more pressure on what little is left of the social safety net.

In its 2019 industrial strategy, the UK launched a “grand challenge” of adding five years of healthy life to each of its citizens by 2035. Medical researchers are now looking seriously at whether the key to defeating age-related diseases is to tackle the underlying issue, aging itself. That puts them in uncomfortable lockstep with a beauty industry that has promised much and delivered little in this space, as well as legions of charlatans since time immemorial.

Scientifically speaking, much of what we think of as aging is the consequence of DNA damage that accumulates in cells over time. Cells with DNA damage can cause problems for an organism. Chromosomal clocks (called telomeres) limit the number of times a cell can divide, limiting their lifespan. Thus aging seems inescapable, a natural limit of biology, so firmly entrenched that we use the same word for both age and infirmity.

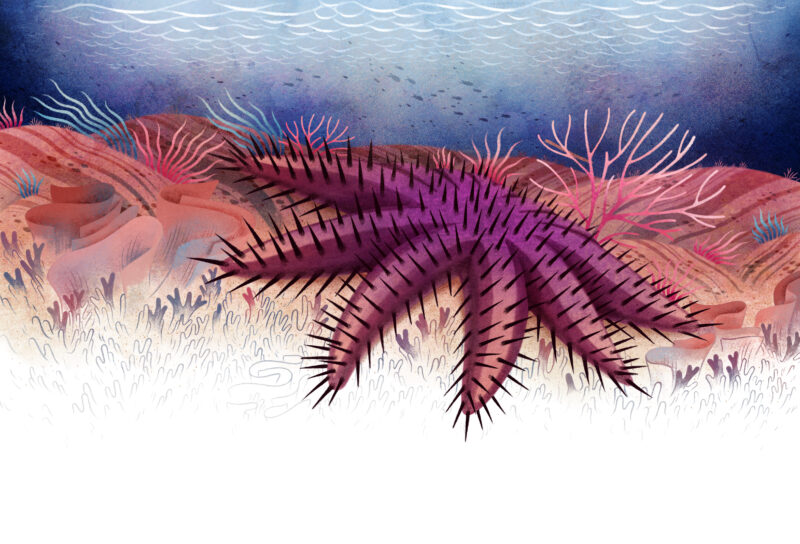

But not all animals grow old. Lobsters, for example, are as strong and fertile at 30 as they are at 2. They only die because they grow bigger with each passing year, until eventually the energetic cost of moulting such a huge shell is too great to bear. Clearly, they have some protective mechanisms that we lack.

Nor do all animals age at the same rate as us. Judy Campisi is a professor of biogerontology at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging. “Different creatures with similar genomes have radically different lifespan,” she says. “A mouse and human are roughly 97% genetically identical, yet have a 30-fold difference in lifespan. What dictates that a mouse lives three years and a human lives 100?” Knowing the answer to that could allow us to extend our own lifespan.

How Would it Work?

When cells approach the end of their predetermined life, some fall into a state of senescence instead of dying, irritating the surrounding tissue. The number of senescent cells in our bodies increases with age, and the long-term inflammation they cause is believed to underlie many age-related diseases such as arthritis. Two key areas of interest for anti-aging researchers therefore are senolytics — which clear the body of these senescent cells — and telomere repair, which should prevent cells falling into a senescent state in the first place.

David’s youthful mice, for example, had been administered a senolytic agent. And in 2012, Spanish biologist María Blasco showed that mice treated with telomerase — a protein that repairs telomeres, increasing the number of times a cell can divide — lived up to 20% longer.

Mike Fossel is president of a biomedical startup called Telocyte, which is seeking approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a telomere-lengthening gene therapy to combat Alzheimer’s. “We have gone out of our way to avoid being labeled an anti-aging company,” he says. “Yet at a fundamental level in some sense that is a contradiction, because the only way we can treat Alzheimer’s is to reverse aging at a genetic level.”

If age-related diseases are found to share a common root in the aging of cells, this may muddy the delineation between healthcare, beauty treatments and life extension. “I don’t think it’s a meaningful distinction,” says Clement. “If you reduce morbidity risk, essentially we’re not growing old in a way that’s going to be detrimental.” In other words: age without aging.

But while increasing healthspan, the amount of time we live free of chronic disease, is seen as a respectable pursuit, increasing lifespan is not. When the UK government invited Mellon to give evidence to an inquiry on healthy aging, his optimism for longevity research was not reciprocated by the assembled peers. Through senolytics, organ regrowth, AI-assisted drug discovery, and gene therapy, he told the assembled peers, humans could live to 150.

“A pipe dream,” huffed Lord Patel, chairing the committee.

“We are aging rapidly as we conduct this inquiry!” another snapped.

This attitude isn’t surprising, says Fossel. “We’re flying in the face of a lot of preconceptions. It’s a conceptual revolution. We anticipate people won’t believe it and won’t want to believe it.”

On the Brink of Legitimacy

The ghost of the snake-oil salesman still hovers over the industry. Ambrosia, one of Silicon Valley’s most notorious anti-aging outfits, offered infusions of blood from young people as a treatment against aging. It shuttered in 2019, following a consumer warning from the FDA (“some patients are being preyed upon by unscrupulous actors”), only to relaunch a few months later under a different name, Ivy Plasma.

As for Parrish of BioViva, there has yet to be any independent verification of her claims to have undergone gene therapy, nor any proof that such a treatment would be safe or effective in humans. The “vaccine” promised to the public at the Longevity World Forum turns out to be an offer to test telomerase therapy in 10 Alzheimer’s patients in a clinic in Mexico, beyond the oversight of the FDA. It will be administered by radiologist Jason Williams, who previously ran a clinic in Alabama offering unlicensed stem cell procedures, before he moved his business abroad following an FDA crackdown.

Even if we find a drug that can prolong our youthful state, we ought to take care when tinkering with one of the fundamental aspects of our biology.

Fossel worries that longevity researchers willing to play fast and loose are risking another “Gelsinger moment,” referring to the death of patient Jesse Gelsinger in a botched gene therapy trial in 1999. “Gene therapy is becoming a garage industry, done by people in labs at an undergraduate level really,” says Fossel. “I hate to think of anyone making a misstep. It would set the field back.”

Leigh Turner, a professor of bioethics at the University of Minnesota who previously reported Williams’ stem cell activities to the FDA, says companies like BioViva are unlikely to bring real treatments to market.

“It’s all about generating froth, generating media articles — as a way of pulling in investors,” he says. This reputation for froth undermines the work of legitimate researchers.

A Disease Like Any Other?

As far as medical regulators are concerned, aging is not a treatable condition. Trials that specifically aim to demonstrate an anti-aging effect are unlikely to be approved. “If you want to explore the anti-aging properties of a drug now, you have to look at something else that FDA does consider a disease and hook your drug on to one of those labels,” explains Clement.

The first anti-aging drugs to reach the market therefore will almost certainly have been approved for other age-related conditions: osteoarthritis, muscle loss, Alzheimer’s. One such drug is metformin, already approved and widely prescribed as an anti-diabetic, and currently the subject of a $65m trial for possible anti-aging effects.

Time itself is an obstacle here. It will simply take too long to demonstrate that any drug can slow aging — or the appearance of aging. “No company can sustain itself for 40 years while they work out if something works in the longevity sense,” explains Mellon. “Every company has to have commercial application to treat the diseases of aging.” Unity’s mouse-rejuvenating serum, for example, is being positioned as a treatment for arthritis. But its effects could be much more widespread. Over dessert in the Parisian hotel, Unity’s Nathanial David assured me: “Everyone will want this drug.”

The greatest hurdle is the reasonable fear of side effects. Even if we find a drug that can prolong our youthful state, we ought to take care when tinkering with one of the fundamental aspects of our biology. Telomere shortening and senescence are not failures of biology but important protective mechanisms. The genetic change that results in expression of telomerase — the protein that repairs telomeres and allows cells to keep on dividing — is a characteristic of cancer cells. Similarly, senescence puts old cells that have accumulated damage to their DNA into stasis before they can become cancerous. This seems like a good reason not to administer either to healthy people.

All’s Well That Ends Well

Even if we found a safe way to defeat age-related diseases, and age without aging, there’s every chance we won’t live any longer as a result. “The public has a hard time grasping the distinction between death and aging,” says Campisi. “They are related, but not the same thing.” Although life expectancy has increased in the last century, and more people are surviving into their 80s, the number of people reaching 90 or 100 has not increased in the same proportion. That hints that there may be other processes at work that limit human lifespan, as yet unknown.

Equally, while senolytic treatments can keep mice looking younger and healthier than their naturally-aging counterparts, they don’t necessarily live longer. Mellon cautions against investing too much in these interventions, saying: “If you cure all these diseases, it would only add a decade. That is not the cure for aging.”

“Part of me does think of aging as a fundamental feature of human life, and that we should be skeptical of anyone who says we can eradicate it,” says bioethicist Turner. “It ties into fantasies of not growing old, not dying. That’s the looming shadow of the conman.”

Despite these reservations, the fight against age-related diseases will likely become the most important health issue of our time. Those of us who expect to be old in the coming decades can only hope that the current cultural shift persists, and eventually marginalizes the idea that being old means being infirm. That may begin to erode the negative cultural associations of aging, and our conflation of beauty and youth. When we see people in their 80s and 90s leading rich, active lives, maybe it won’t seem so terrible to grow old. Maybe it will just seem beautiful.