When my friend H. had twins, I flew down to Melbourne to see if I could help her. The babies had arrived a month prematurely, and the smaller of the two was delicate and tiny. She had come home only a touch above the weight threshold for hospital readmission, and so H. spent the first days of her daughter’s life attempting to establish feeding, intent on helping her baby gain weight.

Arriving at the house, I let myself in, and a familiar voice floated down from the bedroom. “I’ll be down in a minute,” H. called, “I’m just expressing some milk! Don’t come up!” She’d been so comfortable when I was feeding my own son, one breast hanging over the flap of my maternity bra, that I hadn’t anticipated her desire for privacy — but every new mother is different, I thought. I put on the kettle and pottered around while I waited; the morning was golden, glowing, relaxed.

By the evening, her partner was pacing with one baby, while I tried to latch the other onto H’s nipple, and then to a nipple shield, as she winced and shifted forward to reposition her breast. Preemies often have difficulty latching, and H’s breasts were tender and aching with possible mastitis — her face was red and flushed, the babies hiccoughing with rage. We spent the wee hours on the phone to the breastfeeding hotline, all modesty exhausted, as the strength, skill and willpower of three adults went into coaxing two babies to eat.

For some people, breastfeeding comes naturally. For others, it is more of an endurance event. Breastfeeding, as a process, is not always straightforward, and producing enough milk to sustain a growing child — or producing milk at all — can be painful and overwhelming, or despite best efforts, impossible.

I think about the twins, who are now thriving toddlers, when I first speak with Leila Strickland near the beginning of the pandemic. Chatting via Zoom, with both her children and mine home from school — we have carved out little pockets in which to work, something most primary carers are already fairly used to — our conversation is ostensibly about her astonishing breakthrough in cellular agriculture, but dips in and out of our own experiences breastfeeding.

For Strickland, the two are closely entwined. A cell biologist by training, she has spent the past seven years investigating what she calls the ‘intricate choreography’ of mammary epithelial cell dynamics. After struggling to breastfeed her own children, she became engrossed in the question of whether these cells, responsible for synthesising the 2500-odd molecules found in breastmilk, could be coaxed into creating milk in a laboratory setting.

In 2013, the same year that cellular agriculture made its mainstream debut with the public unveiling of Mark Post’s lab-grown hamburger patty, she rented a small lab space, bought a tissue culture hood, and incorporated as an LLC so that she could legally order biological reagents. Initially, the mammary cells she worked on came from cows, “because that was the cheapest source possible,” — everything came out of her own budget, and experiments were conducted around paid work and childcare.

From those first few experiments came a more refined idea — and in February 2020, Strickland, and her BIOMILQ co-founder Michelle Egger, announced that they had successfully identified casein (a protein) and lactose (a sugar) in a proof-of-concept milk sample created from mammary epithelial cells in the lab. The announcement caused a flurry of media attention, suggesting that synthetic human breastmilk was just over the horizon.

By decoupling breastmilk from the breast, Strickland and Egger have opened the door for startling changes in the way we conceptualize gender, labor, and care.

Synthetic, or ‘cultured’ breastmilk, Strickland is quick to point out, will never be able to replicate the complex immunological benefits that are conferred through the human breast. Instead, the aim is to provide a lab-cultured milk that is much closer to the composition of breastmilk than dairy formula, providing a better option for the babies of parents whose own milk output is low, or for whom lactation is otherwise difficult or uncomfortable.

What is most exciting about this, from a social perspective, is that these parents include cis men, and trans and genderqueer parents. A mammary epithelial cell is gender-agnostic, forming in the womb before sexual differentiation occurs. It’s why men have nipples, and why men have been known to lactate in certain medical situations — some pituitary tumours, for example, will raise prolactin levels, triggering lactation.

BIOMILQ envisages both a shelf-stable commercial product, cultured from a blend of ‘immortal’ or commercially available cell lines; and a subscription model, by which new parents could access a supply of accessibly priced, personalised BIOMILQ, stored in sterile conditions and shipped in monthly batches. A person’s cells, taken via biopsy, would not require them to lactate — but would yield a milk that was unequivocally ‘theirs.’

The announcement was significant not just for its technological implications, but because by decoupling breastmilk from the breast, Strickland and Egger have opened the door for startling changes in the way we conceptualize gender, labour, and care.

For a few weeks, Strickland and Egger were in the limelight, with media outlets examining both the science of Strickland’s breakthrough, and the socio-cultural and political factors that ordinarily inhibit breastfeeding. It seemed as though momentum was building for a sustained conversation about the complexities of infant nutrition.

Then the science press turned its attention to the emerging crisis of a historical pandemic, and the BIOMILQ lab temporarily shut its doors. The famous cells were cryogenically frozen, left waiting, like Sleeping Beauty, for someone to come and wake them up again.

Strickland was, for the most part, unfazed, turning her attention towards getting through the pandemic. Her research, built as it was around the realities of motherhood, had always grown in fits and starts. What she hoped for was a pause — time to gather her resources, grow her team, and really drill down into how commercial lab-cultured breastmilk might work.

Imagine a sunflower blooming beneath the nipple — this is roughly the internal structure of the human breast. The ‘petals’ are a person’s milk ducts, which are lined with mammary epithelial cells. These cells absorb nutrients from the mother’s blood supply, metabolically convert those nutrients into breastmilk — a process that generates thousands of unique molecules — and then secretes them into the duct to be stored until the milk is removed during feeding.

Breastmilk is astonishing in its natural diversity. ‘Fore’ milk is often blueish, but can be brown, pink, or green-tinged; ‘hind’ milk is as yellow as cream, with a higher fat content to encourage satiety. For decades researchers thought that breastmilk was sterile, but the discovery of the gut-brain axis has introduced the reality that a profound microbial transfer is taking place between the infant’s lips and the mother’s nipple.

These microbial ‘cues’ are now believed to signal to the body that the increase of a specific component of breastmilk is required. Antibodies in breastmilk increase when a baby is sick; milk’s fat content rises to support a baby’s growth spurt. The flavor of specific foods is also known to affect breastmilk, with some babies finicky about milk that is produced after a person has eaten garlic, while the flavor of bananas apparently lingers.

“Breastmilk is just so complex,” says Michelle Egger. “The biomimicry of it — to try to reverse engineer it, to get to milk, you would never be able to get close, and I mean — it’s just fascinatingly hard.”

As a dairy scientist, Egger is intimately familiar with the composition of cow’s milk, and is still getting her head around the process of human lactation. She credits Strickland with the specialised aspects of the work — “Leila is just an amazing, amazing scientist” — but her understanding of commercial food production, and thorough knowledge of food science, have been invaluable to getting BIOMILQ off the ground.

Egger began thinking about the question of infant nutrition while finishing her MBA, after a semester working with the Gates Foundation in South-East Asia. Counter-intuitively, for a dairy scientist, she spent her time there investigating ‘plant-based protein supply chains’ — alternatives to dairy milk in areas where livestock were too pricey to sustain, or where cultural attitudes towards dairy milk prevented its uptake.

“There’s a huge number of women of childbearing age who are currently protein- energy malnourished,” she says, a little restlessly. “They’re not receiving enough protein in their diets, or are malnourished in general — and we know the first thousand days are incredibly important for a baby. And if a child is born to a mother who is experiencing malnourishment, we see wasting issues pretty quickly…and then you can’t get out of that cycle.”

Part of the issue is that the capacity of the human body to produce breastmilk is limited, not at a cellular level, but metabolically, to preserve a new mother’s health.

“We have all of these biochemical pathways,” she says, “that purposely, if you’re low on nutrients, or you’re having a hard time sustaining your own musculature or fat levels, mean that your body will down-regulate the amount of milk it produces, so that you don’t essentially harvest nutrients from your own body to give to your child.”

The protein-alternative research project was intended to boost maternal nutrition, giving infants a better chance to thrive, but Egger came away frustrated with the slow pace of the non-profit sector.

“It was clear that everyone has the tools they need to start to make really important food systems change,” she says. “But no one is doing it fast enough. It was kind of unacceptable to me, that we would think about a strategy to try to work on something and see if we can get it to go in the next few years.”

A few weeks after returning to America, Egger mentioned her frustrations to a friend — who happened to know Strickland.

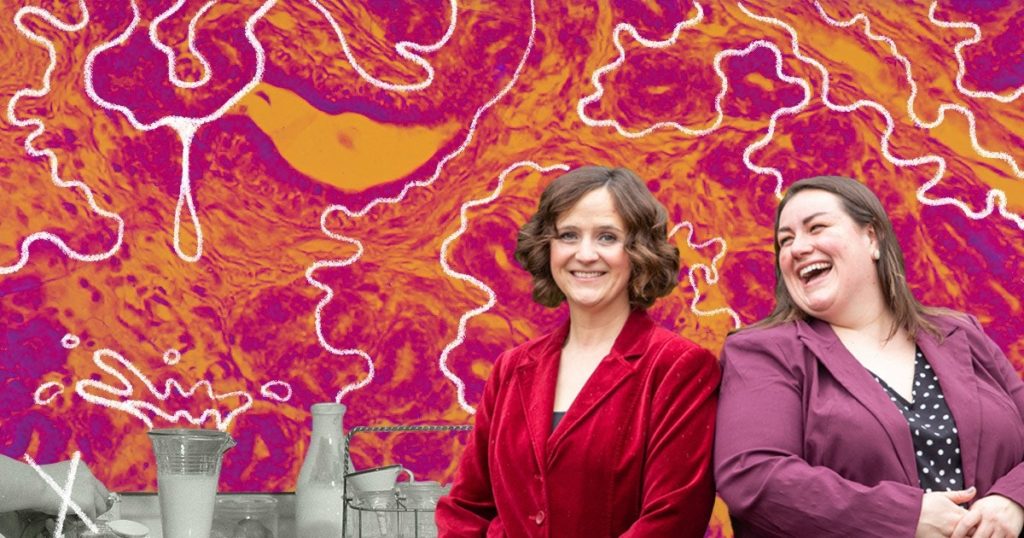

“It felt like the clouds had parted,” says Egger, of the pair’s first meeting. “As cheesy as it sounds, it really has been like finding your better half as it pertains to work…It was just like a hundred volts at the moment where we both realized the depth of understanding, and the complementary skills that we had, to really try to improve things.”

It’s the ability of lab-grown cells to produce breastmilk in ongoing quantities that most excites Egger, who sees in the process a way to circumvent some of the energy depletion that endangers a malnourished mother’s health.

For most of a person’s life, mammary epithelial cells lie dormant, waiting to be activated, for want of a better word, by the changed hormonal profile of pregnancy. Some people find themselves lactating towards the end of their pregnancy, but ‘mature’ milk — a thinned-out version of colostrum, the dense, yellowish fluid that clears out a baby’s meconium and protects their immune system — only comes in three to five days after a person has given birth, and lets down in a closed loop of supply and demand.

Lab cells, on the other hand, can be kept in a constant state of lactation; they will continue producing milk indefinitely, given the right amount of media, which is essentially cell food. No down-regulation is needed — with a constant source of nutrition, cells have no need to conserve energy for themselves.

For Egger, lab-cultured breastmilk seems like an obvious corrective to the bovine-derived infant formulas that dominate the market. Though she is quick to point out that she has nothing against dairy — “I eat yoghurt every day!”, she says — she is skeptical of the extent to which infant formula companies can compete with lab-cultured options. Many market leaders are now attempting the kind of science Strickland is expert in by adding things like synthetic human milk oligosaccharides to their infant formula, but they fall far short of what BIOMILQ envisages.

She also finds the kind of cross-species wet nursing implied by dairy formula more disconcerting than the idea of lab-cultured human milk. “I think, you know, it’s a little strange to think that we actually use powdered milk of another animal, with added vitamins, to feed our children today,” she says, making a face. “To say, ‘We are an animal, and there are other animals, and we have found another animal that we harvest and milk, and dry that milk until it’s powder, and then take it to our homes and blend it up to feed our child.’”

“I think our project makes more sense, and has fewer cognitive dissonance points, than some other modern feeding tools. We’re truly just making milk outside of the body,” she adds. “Everything about this, when you truly start to understand the process and the work, fundamentally makes sense.”

In talking to Strickland and Egger, it becomes increasingly clear to me how fine the needle is that they have had to thread, as two female scientists at the helm of a small, independent team, in order to secure the funding needed to make BIOMILQ feasible.

Early on, Strickland made the deliberate decision to be upfront about her own difficulty breastfeeding, establishing her role as a mother, as well as her scientific credentials, as a crucial part of her professional persona.

“My daughter was born in January 2013, and I think we actually opened our lab in October of 2013,” she tells me, when I ask about how closely her experiences guided the scope of her research. “I was still trying to breastfeed her, mainly pumping milk at the time. I remember thinking a lot about my own personal predicament, never being able to produce enough milk, having a lot of anxiety about my milk supply and a lot of discomfort needing to pump constantly in order to keep it going.”

“At the time, I felt isolated,” she adds. “It felt like in my circles, everyone else was doing fine — like, compared to all these other new mothers, something had to be wrong with me.”

Speaking openly about that feeling has been an important way for Strickland to connect to potential supporters. At the same time, both women have been anxious that BIOMILQ not be relegated to a perceived niche market, something that’s ‘for moms,’ meaning fundamentally unserious. (Though I knew that the sector was male-dominated, it wasn’t until I started researching this story that I realized just how male-dominated it is; Reneeta Das, writing for Forbes in 2019, claims that 94% of decision-makers in US venture capital firms are men.)

“I think there are a lot of mothers who are in the predicament of feeling like they have to make a trade-off between what they are told is best, and what they’re practically able to accomplish.”

Leila Strickland

Any product that positions itself as a parallel option to breastfeeding will come under not-unwarranted scrutiny. Strickland and Egger both go to such lengths to assure me that BIOMILQ is not intended supplant breastfeeding, that I wonder if they’ve had bruising experiences around the question in the past. There are times when this insistence seems less about upholding the medical orthodoxy, and more about navigating and potentially defusing social and cultural pressures.

Strickland, especially, seems ambivalent about the place that breastfeeding has come to occupy in the cultural consciousness, something that fueled her own anxiety and guilt around supplementing with formula.

“The idea that ‘breast is best’ is constantly coming at us, from family members and pediatricians, and it can be really pervasive,” she says. “I think there are a lot of mothers who are in the predicament of feeling like they have to make a trade-off between what they are told is best, and what they’re practically able to accomplish.”

“When we talk to mothers, their reasons for shifting to formula or supplementing with formula aren’t related to their lack of knowledge about the benefits of breastfeeding,” she adds a little impatiently. “At a certain point, you’re just giving women more things to feel guilty about. We’re still trying to understand all the benefits of breastfeeding, but it doesn’t matter what the benefits are if a woman can’t do it.”

And many people, for various reasons, can’t. For one thing, the amount of milk that anyone person will be capable of producing is more or less a mystery — there are few ways to predict it in advance. Some women produce milk abundantly, and deal with the attendant soreness and leaking; others struggle to maintain a consistent supply.

Cracked nipples are common, as is thrush, which passes back and forward between the nipple and the baby’s mouth. Infants with a tongue-tie will often have trouble latching; engorged breasts are painful, ducts are easily blocked, and milk blebs or blisters can form on the nipple, which feel like shards of glass.

In a small number of women, let-down — the hormonal signal to the body to release milk into the ducts — comes with an intense anxiety, fear, hatred of the baby or even suicidal thoughts. Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex — D-MER — lasts anywhere from 30 seconds to two minutes, coming and going so swiftly that a woman might doubt herself completely. It’s thought to have something to do with inappropriate dopamine activity, but study of the condition is thin.

When I was in the depths of my own early motherhood, breastfeeding felt easy — one of the few things about the postpartum period that did. Latching a crying baby to the breast took less than five seconds, and the thought of getting out of bed to stand in the freezing kitchen and mix formula was profoundly unappealing. I can understand, though, why a person might choose not to breastfeed, even if they are capable of doing so. The phrase that a lot of maternal and child health nurses use is ‘touched out’ — early parenthood can be so demanding, with so many tiny violations of a person’s sense of autonomy, that physical touch beyond a certain threshold becomes almost unbearable.

A person might simply want to return to work — to share the feeding load with a partner or family members — or may need, desperately, a full night’s sleep. Pumping breastmilk can accommodate these needs, but pumping still places demands on the maternal body — and the noise of the pump can make you feel like you’re losing your mind.

In the past, women have dealt with the issue in one of two ways — either by supplementing with animal milk, pap, or cereals cooked in broth, or by hiring a wet nurse to take over the labor of breastfeeding. Wet nurses are listed in census data up until the 20th century, when infant formula hit the market, and the profession disappeared — but some parents continue to practice a kind of informal contemporary wet nursing via ‘milk kinship’, sharing or selling excess breastmilk online.

Difficulty breastfeeding is recorded in pediatric literature dating to the Tang Dynasty, and the authors of a survey in the Journal of Perinatal Education note that lactation failure is mentioned in the earliest known medical encyclopedia, The Papyrus Ebers, from Egypt (1550 BC). This volume contains a small pediatric section that includes a prescription for lactation failure, as follows:

To get a supply of milk in a woman’s breast for suckling a child: Warm the bones of a sword fish in oil and rub her back with it. Or: Let the woman sit cross-legged and eat fragrant bread of soused durra, while rubbing the parts with the poppy plant.

Supplementing with a dairy-based formula seems preferable to rubbing oily fish bones on one’s back. But, as Strickland notes, the basic ingredients of infant formula haven’t changed for a very long time.

“This hasn’t been an area where there’s been, any innovation,” she says. “We hear from moms all the time, who are excited that there’s a company that really understands the challenges, and is working to disrupt the status quo of what options we’ve had for all this time.”

The mainstream understanding that breast milk substitutes don’t sufficiently meet infants’ needs is a relatively recent one, ushered in by The Lancet’s landmark series on maternal and child undernutrition, in 2008. Though doulas, midwives and family matriarchs have long championed breastfeeding, it has taken longer for entrenched cultural attitudes to change.

The crucial ‘first thousand days’ that Egger mentions in our conversation refers to what is now conventional wisdom — the idea that healthcare received while a child is in utero and in the first two years will set the benchmark for lifelong outcomes. As such, the World Health Organisation recommends exclusive breastfeeding to the age of six months, and extended (mixed) feeding for two years and beyond.

Breastfeeding, from a relatively unremarkable practice, has become the standard for healthy child development. The idea that ‘breast is best’ is one that Strickland finds disproportionately dominant, but she is keenly aware that BIOMILQ is stepping into a space that has historically caused irreparable harm.

In 1973, the New Internationalist published an exposé of the ways in which infant formula companies strategically created and then exploited demand for their product in urbanising countries, encouraging women to ‘modernise’ by moving away from breastfeeding in favor of the ‘scientific’, ‘hygienic’ formula.

Multinationals such as Nestlé, which had already become a flashpoint for boycotts, used unscrupulous tactics such as hiring ‘milk nurses’ dressed in uniform to distribute samples to new mothers in hospitals, a practice which disrupted the establishment of milk supply. When hospitals banned the milk nurses, they simply waited outside, or doorknocked in areas where clean nappies hung out like flags on the clothesline.

Through the industry’s strategies, wrote Edward Baer, ‘formula marketing systematically undermined its ‘competition’, breast-feeding, at both psychological and physiological levels.’

Promotional campaigns have encouraged the view that breastfeeding is complicated and prone to failure. Breast-feeding is thought of negatively on the basis of beauty (breast sag); work (you have to stay home); snob appeal (only the peasants do it); racism (white women don’t breastfeed); and fear (it won’t work, your baby will starve).

These insinuations would be harmful in and of themselves, but what such caused a scandal in the 70s — and what remains almost incomprehensibly distressing—is that these strategies were knowingly deployed in areas where, due to poor sanitation, the use of infant formula would almost inevitably compromise an infant’s health.

Unlike breastmilk, formula needs to be prepared outside the body, and if conditions are not adequately sterile — if the water added to powdered formula is carrying bacteria or infectious disease — if women living in poverty stretch each tin as far as it will go, then the outcomes for babies are disastrous.

In 1981, the World Health Assembly adopted the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes, or WHO CODE, prohibiting direct marketing to new mothers and ensuring that all claims made for the benefits of infant formula were objective and based in fact.

Though in many countries direct marketing has been explicitly banned, a 2019 advocacy paper released by the Global Breastfeeding Collective points out that the Code has not been uniformly implemented, with ‘countering [the breastmilk substitute] industry’s marketing practices’ considered a ‘top advocacy priority.’ Violations they cite include:

- using advertising and social media to promote BMS, bottles, and teats to the general public and to health-care systems

- distributing free samples to mothers

- enticing customers to buy BMS products using sales inducements such as special offers or price reductions

- publicizing health claims on labels or other BMS materials

- idealizing BMS products in text or images

- providing free supplies of BMS, bottles, or teats to health facilities

- and sponsoring the education and meetings of health workers.

In other words, the ‘milk nurse’ has been replaced by the influencer. Where images of bare breasts are still policed on social media platforms, the formula industry has a particularly strong advantage, diffusing images of plump babies and toddlers across social networks, where formula ads are algorithmically directed towards women aged 18-35.

*

Both Strickland and Egger are aware that a product such as BIOMILQ can only do so much to turn the tide on infant nutrition. Race, class, export policies, government subsidies, and public health initiatives all influence a person’s capacity to breastfeed, as do workplace policies and legislation around parental leave and breastfeeding accommodations. A statistic that BIOMILQ cites in its publicity is that 84% of breastfeeding parents transition to dairy-based infant formula before the recommended six-month exclusivity period — and both women are keen to talk about structural, as well as biological, reasons why.

Posts on the BIOMILQ website draw attention to others who are tackling structural issues; recently, during Black History Month, the team posted a tribute to Black women who have worked to support maternal rights and nutrition, some of whom have been mistreated or exploited by the scientific industry at large, alongside a recommendation for Andrea Freeman’s Skimmed. They have also posted about medical gaslighting, and the politics of ‘lactivism,’ in between short missives explaining the science behind the product.

The pair use the words ‘parents’ and ‘mothers’ alternately, as I have in this article, and recognize that not all breastfeeding parents are cis women. Where some people can breastfeed and choose not to, there are others for whom the production of breastmilk might be a long-held dream — or at least a way to feel biologically involved in the care and nurturing of a child.

“We are very excited to have the opportunity to talk about gender roles,” Strickland says. “We’ve talked a lot about doing this with men’s cells. In fact, my husband has the first right of refusal.” Other men in Strickland’s circle, including a gay male investor, have asked if they could be involved in the upcoming trials.

Some trans women already induce lactation, following the Goldman-Newfarb protocol, and a few lesbian friends of mine have induced lactation, too, so that they can share the labor — and the intimacy — of breastfeeding with their partners. A product like BIOMILQ might similarly support trans men who are ambivalent about chestfeeding, or allow fathers to step into the breach during periods of postpartum depression or illness.

Redirecting lactation from the body to the lab means that breastmilk is no longer off limits for people who want to produce milk, but who for reasons of dysphoria — or physical complications like an elevated risk of cancer — are wary of changing their hormonal profile in any significant way. It means that adoptive parents of babies can experience something close to breastfeeding their infant children.

There is comfort in knowing that there are women out there thinking about early motherhood, about infant nutrition, and about ways to alleviate trouble when it comes.

When I think of my own experiences of breastfeeding, I remember the physicality of it — the strange rhythms, the stickiness and warmth. Perching on a table at a book launch, the only possible place to sit and feed, with a newborn at the breast; my late grandmother referring to me once, apparently without malice, as ‘the dairy’; the look of quiet revelation on my husband’s face when he bottle-fed our infant for the first time (“Jessica! I’m feeding our baby!”). You don’t need a cell biopsy for that, or anything other than love.

There was softness, and sometimes comfort, in having my own child on the breast, one that sometimes made a moment of stillness and reprieve. Had I been thinking a little more clearly, I’d have realized that switching to formula would give me access to stronger antidepressants; but I don’t regret the long nights of feeding, though most of them were lost within the fog.

At the same time, I think if I were to do it again, I’d be assured by the knowledge that a product like BIOMILQ existed. At the very least, there is comfort in knowing that there are women out there thinking about early motherhood, about infant nutrition, and about ways to alleviate trouble when it comes.

A few months into the pandemic, the BIOMILQ lab opens up again, with a $3.5 million investment secured from Breakthrough Energy. Egger launches a recruitment round, and the team begins to grow. With the funding, too, comes an increased disinclination to dance around the attitudes they faced before finding a ‘mission-aligned’ investor.

“You don’t have to be a woman or a mother to care about these topics or to think of solutions,” Strickland writes in an early email, “but on the whole, these are issues that the biotech industry hasn’t been particularly interested in or concerned with.”

Off the record, towards the end of one of our chats, she tells me a few horror stories, including a meeting with a potential investor who asked why women ‘didn’t just get a wet nurse’. Her expression — a mix of exasperation and chagrin — is mirrored on my own face through the screen. On BIOMILQ’s first birthday, Strickland posts to the website, sharing more explicit details about her time spent trying to convince ‘slick young biobros’ that the technology she pioneered had merit.

‘Most of them were wealthy white men from Silicon Valley,’ she writes, ‘who had scarcely ever considered the purposes of breasts beyond the ornamental, some of whom clearly only attended the meeting for the boob jokes…Some of them were more attuned and made sure I knew it by mansplaining the various challenges of breastfeeding to me…There’s a gross disconnect between the challenges of early-motherhood, and those with the power to support struggling moms.’

Seven years is a long time to dedicate yourself to a vision of something radical, maybe impossible, when those around you can’t necessarily see it. Over the past few years, a handful of other start-ups have appeared with the same stated goal, something which both Strickland and Egger speak warmly and enthusiastically about.

TurtleTree, which was a very close early competitor, has pivoted towards commercially creating lactoferrin, a protein which may help inhibit COVID-19 — but the company still expects its first breastmilk product will be available within a few years’ time. The closely named Israeli start-up Bio Milk has just floated, and the New York-based Helaina is exploring a yeast-based fermentation approach, meaning that the field has become increasingly competitive.

“It’s been incredibly validating, in a lot of ways, to have at least one other group out there on the other side of the world thinking, ‘Maybe you can make milk from mammary cells’, you know,” says Strickland.

Because it turns out that maybe you can. Last month, an announcement pops up on the website — proclaiming unequivocally that BIOMILQ has successfully made its first independently-evaluated human milk. “We can now confirm that BIOMILQ’s product has macronutrient profiles that closely match the expected types and proportions of proteins, complex carbohydrates, fatty acids and other bioactive lipids that are known to be abundantly present in breastmilk,” they write. In the publicity photo that accompanies the press release, Strickland and Egger are beaming.

In some ways, this is where the BIOMILQ story begins — again. Now that the proof of complexity has been met, and the company’s funded, the challenges that Strickland and Egger will face have changed, with some remaining out of their hands. The issues now will come from being the test case for a new category of food, one which requires a support network that is still in its infancy, challenges social and cultural attitudes, and will put stress on the flexibility of regulatory agencies.

“I think, have a pretty sober understanding of kind of the regulatory challenges that we’re likely to face,” says Strickland. “We’re trying to starting those conversations, as learning more and more in the lab every single day. It’s just incredibly fast-paced, but also, the more we learn, the more we discover what we still need to learn.”

It is clear, though, that this is where Strickland thrives. She still lights up when she talks about cytology. “I just think that cells are so beautiful,” she says, smiling at me through the screen. “I’ve always felt such a sense of wonder watching them, and thinking about how they have evolved. Mammary epithelial cells, in particular, are such a powerhouse of biosynthesis…I’ve always wondered why we aren’t thinking more about mammary cells.”

She is in the process of talking with academic groups about potential collaborations that use the BIOMILQ process as a lactation studies, looking at how variables like genetics, stress, and diet might affect the composition of breastmilk. “Alongside our work to understand our own product,” she says, “we’re actively investigating human milk itself, really realizing that there are some important knowledge gaps to be filled. As a contribution to scientific research, we’re going to be in a very good place to help to understand the composition of milk.”

For Egger, who became a food scientist in part because of her love of feeding people, the chance to contribute to a body of scientific literature is gratifying, but the goal remains clear — it is all about getting an improved form of infant nutrition into the world. Her work now is in looking at packaging and distribution, as well as ways to safeguard the bioactive components of the milk.

When I ask her about the timeline, she throws up her hands in mock despair: “You and everybody wants to know!” Beneath the joking — and she jokes around a lot — she is quietly confident that BIOMILQ could become a commercial reality within the next five years, and at a similar price point to high-end commercial infant formula.

“There’s a world in which I envision where you could go to any grocery store and buy the product someday,” she says, her eyes on the horizon. “Maybe I’m a little bit more optimistic than others would be, but the world changes rapidly — and I think the world is catching up with us.

“As a young woman who expects to have kids herself, I’m racing my own timeline to a certain extent,” she adds, “because I never want to be faced with the choice of breastfeeding or bust. We deserve something better. We deserve it. It’s time.”