In the shadow of Cape Town’s Table Mountain, a fire licks its way through a felled pine forest. Amber flames coil around a stump and slither to its roots. A molten half-tree collapses. Living and long dead things snap, crackle and pop, above and below ground. The black smoke becomes grey as it engulfs green shrubs and brown earth until all is a thick pure white.

This may sound like devastation, but it could be the start of a resurrection. The real action is happening in the soil. The City of Cape Town set this prescribed ecological fire to burn through layers of colonial agriculture, in the hope that it might reinvigorate the dormant seeds of an indigenous plant buried below. If all goes according to plan, a flower long thought extinct — the imposing Leucadendron grandiflorum — could rear its golden head for the first time in at least half a century.

Phoenix or Phantom

The beautiful 8-foot flower, known as Wynberg conebush, once thrived on these hills. Back then, the land was rich with a unique type of vegetation called Peninsula granite fynbos — a dense and diverse scrubland of aromatic herbs, delicate succulents, and towering shrubs — a rare habitat particular for its close relationship to fire. The pastoralist Khoikhoi, the first settlers in the region, understood this relationship. They used to burn the soil regularly to rejuvenate it for livestock grazing. This tradition continued for millennia until the establishment of an outpost by the notorious Dutch East India Company in the cape displaced Indigenous communities. The Dutch planted neat rows of wine and wheat on these hills, the regular burns ceased, and the local ecology began to suffer. In time, the Leucadendron grandiflorum disappeared from the landscape, along with great swathes of its native habitat.

Perhaps fire, its old friend, can bring it all back? That’s the hope of Anthony Roberts, CEO of Cape Town Environmental Education Trust (CTEET). Roberts first conceived of this experiment in 2016 when he drove past a pine plantation on Wynberg Hill and saw that trees were being felled. He happened to know that this hill was the first place — and possibly the only place — that Leucadendron grandiflorum had been ‘sighted’ in the wild. The plantation ensured that this land had been virtually untilled for three quarters of a century, leaving a chance, albeit slight, that a viable seedbank lay beneath the soil.

He approached the current occupants and somehow convinced them to turn the two and a half hectare plantation into a conservation area that might not only recover the Leucadendron grandiflorum, but also restore some of the flower’s valuable habitat. The conditions for fynbos’ germination, however, are highly specific. You need rich enough vegetation to ensure fires of high enough temperatures to produce just enough smoke — all before the rains fall. Roberts had to wait over three years for the right moment: 2018 was too wet; 2019 was too dry; and in 2020, the pandemic shut down everything. Finally, in March 2021, the planned fire could proceed.

In its aftermath, there’s nothing left to do but wait for the phoenix to rise. There is a small problem, though: The phoenix may turn out to be a phantom. Even if a yellow flower does appear on these grounds, how will anyone know it’s the real Wynberg conebush? Unlike most botanical species, there is no original “type” specimen to reference. There is only an illustration of the flower from the early 19th century, a muddled history of rival taxonomies, and a wealth of unreliable claims spanning two centuries. Leucadendron grandiflorum is a mystery buried in a mystery — a palimpsest of the strange ways that science and colonialism have related to the natural world. It is a story worth getting to the bottom of. But for this we’ll have to dig deep, and work through more than a few layers of history and myth.

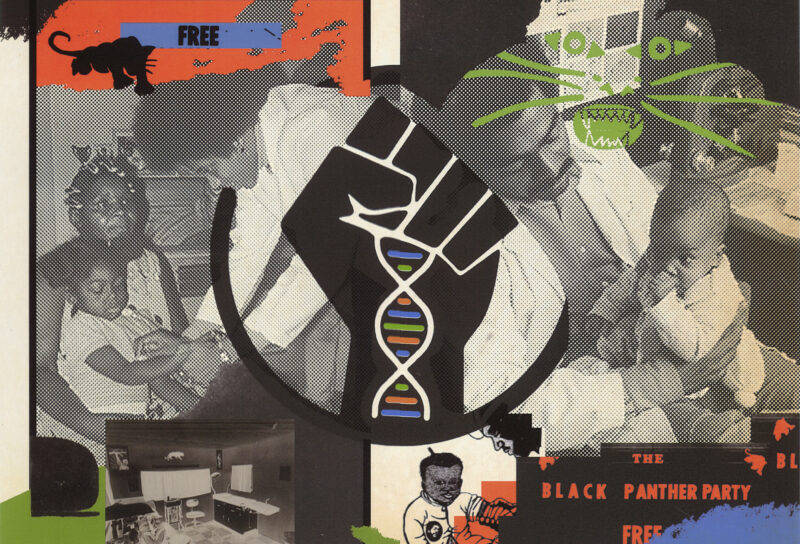

Euryspermum grandiflorum illustration from The Paradisus Londinensis: Or Coloured Figures of Plants Cultivated in the Vicinity of the Metropolis, London: Printed by D.N. Shury, and published by William Hooker, 1805-1807. This plant shown here is now thought to be the ‘Leucadendron grandiflorum (Salisb.) R. Br.’.

The Colonial Catalogue

Western colonialism is remembered primarily for its subjugation of people, but its domination of the land was just as prolific. In South Africa, as throughout the continent, European settlers explored, catalogued, and seized the most productive land, clearing indigenous vegetation with little thought to the consequences. Their attempts at industrial farming would turn much of the Cape’s rich environment into a dust bowl, where terrible droughts, overwhelming wildfires and lasting food and water shortages became the new normal. To add insult to injury, many of the men responsible for the exploitation of this ecosystem anointed themselves the only experts on its spoils.

According to some reports, the Wynberg conebush was ‘last seen’ not in Cape Town but among the London holdings of one George Hibbert—a wealthy politician, slave owner, amateur plantsman, and keeper of an extensive, private garden at his Clapham residence. Hibbert received the flower from James Niven, a young Scottish botanist and collector, who had arrived in the Cape of Good Hope in 1798, when the natural environment was already undergoing a seemingly irreversible transformation. Perhaps Niven was aware of the flower’s tenuous hold on survival when he carefully collected its seeds and sent them to his patron. In his 12 years in the Cape, Niven sent so many new plants to Clapham, that Hibbert likely presided over the world’s largest collection of Proteaceae specimens.

Another strange colonial impulse: the urge to adoringly catalogue what one is destroying.

After helping decimate it a tiny bit more, these men ensured that the existence of the Wynberg conebush would be recorded for posterity. Another strange colonial impulse: the urge to adoringly catalogue what one is destroying. Hibbert gave a male plant of the species to botanical illustrator William Hooker, who contributed a drawing of it to The Paradisus Londinensis, a book on the cultivated plants of London by famous but divisive botanist Richard Salisbury. Salisbury described it as “the handsomest species of the genus yet discovered,” despite its “strong disagreeable smell.” Hibbert and Salisbury had thus released the plant into a new, toxic environment — London’s botanical elite — and this is where we start to lose its trail.

In a scramble to classify the empire, England’s plantsmen were at the time locked in bitter competition. Though distinguished and well-known, Salisbury was fiercely protective of his taxonomic interpretations and no stranger to botanical disputes. When a younger rival, Robert Brown, presented a series of lectures to the Linnean Society revising Salisbury’s earlier classifications, this amounted to shots fired. Brown’s more technologically advanced study was quickly accepted by the wider botanical community, and the outraged Salisbury couldn’t stand for it. He surreptitiously copied Brown’s lectures, quickly revised them, and then published the work under the guise of Hibbert’s gardener, John Knight, beating Brown’s book to the press. Of course, his actions were discovered, and he was ostracized from the community — though not before leaving an indelible mark of confusion on the taxonomy of the species.

The flower Anthony Roberts patiently awaits is the one that Hooker drew and Salisbury described. The trouble is, Salisbury actually named the flower Euryspermum grandiflorum. And although Brown soon renamed it Leucadendron grandiflorum, which became the prevailing name, the damage was done. This disarray has sent lasting ripples through the centuries, with drawings and specimens in herbaria around the world misidentifying or mislabeling other flowers as Leucadendron grandiflorum. A few “great men” of botany left behind an even greater confusion in the scientific ordering of these unique plants — an order which conservationists, ecologists, scientists and scholars rely on to understand and protect the natural world.

And so Roberts finds himself on the receiving end of a taxonomic game of telephone. Not only has he never seen the flower he’s looking for, he’s never seen depictions or descriptions of the plant in its early stages. To complicate matters, the landscape has changed drastically since Niven arrived here some 200 years ago. What used to be Wynberg Hill has almost certainly shifted, and the original location could be anywhere up to two kilometers north, south, east or west of the current site. At the very least, Roberts draws hope from the fact that the soil type is the same — still rich, deep earth formed from broken down granite.

A Whiff of Extinction

Strangely enough, the fire on Wynberg Hill is not the first attempt to bring Leucadendron grandiflorum back from the dead. Or at least, some part of it. In 2014, Jason Kelly, CEO of Ginkgo Bioworks — the company that funds this magazine — attended a convention on essential oils and aromas. In conversation with a consultant for manufacturer Givaudan, who was showcasing their scents of obscure plants, Kelly had a curious idea: What if the same could be done with extinct plants? How might that work? What could that mean? He shared these ideas with his creative director, Christina Agapakis, who put together a plan of action. She studied the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of extinct plants, and was soon leafing through the Harvard University Herbaria for suitable specimens.

One drawer contained a beautifully preserved flower. The label stated that it was Leucadendron grandiflorum — one of the extinct species Agapakis had outlined on the Red List. A cultivated plant taken from the Kirstenbosch Botanic Gardens, it had been displayed at the 17th International Horticultural Congress in Maryland in August 1966, courtesy of one H.B. Rycroft. A professor of botany at the University of Cape Town and a driving force behind the study and appreciation of South African plants, Rycroft may have brought the specimen with him as an exhibit for his paper, “The Horticulture of South African Indigenous Plants.” The Red List assessment suggested that the plant probably went extinct in the late 1800s, so this new date of 1966 was as baffling as it was promising. Could it be that the flower had become extinct much later than initially thought? Was it actually ‘last seen’ in apartheid-era Cape Town?

Not fully aware of the convoluted botanical history in front of her, Agapakis gently removed a fraction of a leaf from the dried specimen. And with the DNA of fourteen extinct plants under her arm, she headed back to the lab.

Once an organism dies, its DNA starts to degrade, and Ginkgo’s synthetic biologists initially had trouble coaxing enough data from the aging samples. Luckily, their friends over in the Paleogenomics Lab at the University of California, Santa Cruz, were able to break down the samples to an even finer level. With this improved surface area, Ginkgo’s sequencing machine was able to read the plants’ genetic code. The sequences were inserted into yeast cultures, which produced smell molecules. Only four of the fourteen specimen elicited viable molecules; one of them was Leucadendron grandiflorum. After more than two hundred years, the flower’s scent (so disagreeable to Salisbury) was once again up for interpretation. The sample produced aromas ranging from cannabis to jasmine — each good on their own, but a little odd in combination. Agapakis and her team couldn’t determine the exact quantities at which the flower produced these aromas. But they had created enough of an approximation to say that part of the Leucadendron grandiflorum was alive again.

Some species leave such an impression on us, even from beyond the grave, that they ensure future attempts at propagation.

Looking to share this blast from the past with a wider public, Agapakis approached Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, a multidisciplinary artist, and Sissel Tolaas, a smell researcher and artist. Together they created Resurrecting the Sublime in 2019 — a collaborative art installation utilizing the smells Tolaas had reconstructed from the DNA. They showcased the scents of three extinct plants in a strikingly bare diorama, featuring only rocks, and synthetic soundscapes of the lost habitats. Visitors were invited to feel the full impact of the loss — landscapes that could only be heard, flowers that could only be smelled — and contemplate how human actions had caused the demise of entire species.

Working on Resurrecting the Sublime, Ginsberg started piecing together the story of the Leucadendron grandiflorum, gathering accounts and filling in gaps. One day, she noticed that the three images she had of the specimen — from Harvard’s Herbaria, the Linnean Collection in Sweden, and Kew Gardens in England — looked strikingly different. Perhaps the flower had just been preserved at three different stages of its life. But what if they were three different species altogether? Surely the Herbaria specimen — the one that Ginkgo Bioworks had spent a considerable amount of time and effort to partially resurrect — was an authentic Leucadendron grandiflorum?

To be absolutely sure, Ginsberg got in touch with Tony Rebelo, a leading authority on the Proteaceae family. Rebelo, who lives in Cape Town and works at the South African National Botanical Institute (SANBI), looked at the image of the Harvard specimen that Ginsberg had sent him and without hesitation said it definitely was not Leucadendron grandiflorum. In his opinion, the specimen was either Leucadendron sessile or Leucadendron tinctum…neither of which are extinct. In fact, he said, Hooker’s illustration and Salisbury’s description in Paradisus Londinensis — and a complimentary mention in Flora Capensis of 1860 — were the only evidence of Leucadendron grandiflorum’s existence. Perhaps it never existed in the first place. How did this phantom arise, disappear again, and still leave enough traces to draw attention until this day?

Concentrated Hubris

Even if the towering golden flower remains forever shrouded in mystery, it nonetheless tells an important story — a cautionary tale about hubris: about how one knowledge system gave itself supremacy, believed itself to be neutral, objective and all-knowing, and became so self-referential that it created its own echo chamber. Starting in Hibbert’s overflowing garden, the confusion around this flower can be seen as a consequence of the colonial rush to seize and categorize as much of Africa’s natural wealth as possible. Commodification precludes care; when you strive to possess something, you rarely see it very clearly.

If the Wynberg conebush did exist, it was part of the natural world of the Khoikhoi long before the first Europeans appeared on the southwestern shores of Africa. Those early pastoralists understood their ecosystem far better than the settlers who displaced them ever could, passing on plant knowledge matrilineally over the generations. Possibly, then, the answer to the current ecological crisis is not only returning this soil to the fire but returning this land to the expertise of its most capable stewards.

Everything else is another experiment, like the hopeful one now happening on Wynberg Hill. As the fire dies down, City of Cape Town employees clad in blue overalls and white balaclavas emerge from an impressive layer of ash. A drone flies overhead, checking for hotspots. A few stumps still stubbornly smolder. Anthony Roberts looks at the dying fire, and wonders whether it created enough heat and smoke to rouse a gigantic flower from the dead. If he fails, others will continue the search for lost beauty. This is the other story of Leucadendron grandiflorum. Some species leave such an impression on us, even from beyond the grave, that they ensure future attempts at propagation.