A decade after the first states legalized recreational cannabis, American weed culture is in the last gasps of its decadent era — giving up a life of fun for a phase of pharmaceutical stability.

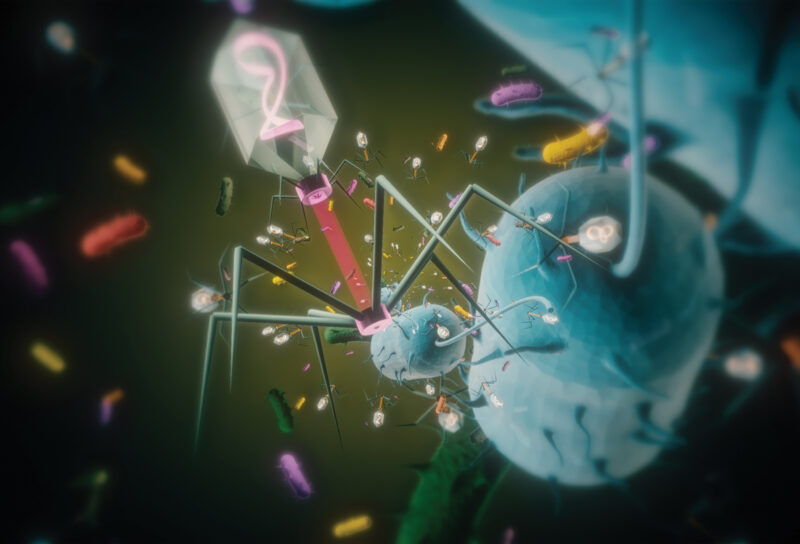

The $10.8 billion market has fluffed that inscrutable stuff you used to buy off a disheveled guy on a bicycle into a flurry of lifestyle products engineered for your self-optimization. The next phase of its evolution will be less trendy, but possibly more trippy. Think: genetically modified weed, super-plants that flower all year round, “skinny” strains that curb your appetite. Scientists are trying to bio-hack this ancient plant, demystify its biochemical composition, and refashion it to deliver targeted, custom highs. The goal in the long run is a new class of strains that treat symptoms as reliably as pharmaceutical medicine.

This new wave of sci-fi weed is not far away, and Big Pharma is investing millions into the science that would shuttle it into the mainstream, possibly replacing the super-charged but scattershot strains we’ve gotten used to. But if this once-mysterious plant loses its ineffability to a DNA-enhanced model of analysis and reproduction, would it even still be the same thing? What do we stand to gain from splicing the mystery out of marijuana, and what would we lose along the way?

The Perfect High for Coding

To taste the rainbow of tomorrow’s pot market, you go to Hall of Flowers, a California trade show where the gentrification of marijuana has reached its latest extreme. Imagine a music festival inside the world’s biggest dispensary and you’ve got it: the Coachella of cannabis. Individual tickets cost $750. DJs spin house music next to decked-out party buses. Stylish stoners in bucket hats lounge in shaded cabanas, sipping sparkling THC water and puffing on pre-rolls of the latest “strain drops.” More than an industry event, where dispensaries discover new brands, this is a weed wonderland where the hype machine is on full blast.

On an afternoon in May, a shuttle bus full of weed influencers drops me off at the Palm Springs conference’s entrance gates, where I shuffle through the security line, relieved not to have to hide my vape pen. I follow the fog of skunky smoke billowing from the consumption area — an AstroTurf lawn covered in orange bean bags, where grizzled ganjapreneurs with arms full of tribal tattoos talk shop with perfectly coiffed publicists. In the cacophonous event hall, weed brands display their goods: Pure Beauty’s menthol joints, Sundae School’s yuzu-flavored mochi gummies, Beed’s Nespresso-like machine that spits out perfect pre-rolls. One dominant trend is impossible to miss: instead of hawking popular weed strains like Blue Dream or Purple Kush, brands are selling experiences — describing products with labels like “CREATIVE” and “COOL” to suggest the feelings they could elicit.

Recreational cannabis is being pitched as a panacea that can do it all: boost productivity or put your brain on mute, send you to sleep or keep you wired, dull your senses or kick them into hyperdrive. In today’s post-legalization marijuana market, there’s a product for every type of need — including some you didn’t even know you had. Wanna get high and horny? Lavish yourself in Kiva’s THC-infused edible body chocolate! Can’t fall asleep and want to lucid-dream? Check out this CBD tincture to help you “drift off into the ethereal,” from Icelandic band Sigur Ros. The science behind these claims is scarce and hardly the point. As weed goes from sanctioned substance to lawful lifestyle product, the versatility of its multifaceted high has made it infinitely marketable — a wellness wonder-drug for both hedonists and the health-conscious alike.

This move towards what the industry calls “effects-based marketing” has been years in the making. In the early days of legalization, writes cannabis PR guru Rosie Mattio in Rolling Stone, the industry often relied on consumers’ knowledge of perennial strain favorites like OG Kush and Sour Diesel. But strain-based marketing was confusing to newbies, Mattio argues, and as the market matured, brands began to sell feelings instead. Canndescent was one of the first weed brands to name its strains plainly after the effects they’re supposed to bring about. There’s Create (for “when it’s time to paint, jam, or game”), Cruise (to “keep up the pace, relax your mind, and sail through the day”), and Connect (for “when it’s time to laugh, go out with friends or get intimate”), among several others. This strategy proved so effective that many other brands followed: for example, Kiva’s popular gummies promise to make you feel “Chill,” “Lucid,” or “Social,” while OLO’s sublingual strips offer moods like “Focus,” “Social,” and “Active.”

The funny thing about this kind of prophetic branding is that it can be self-fulfilling. If the label on a weed strain tells you that you’re about to be creative, it’s a subtle push in that direction. For now, effect-based claims are often based more on anecdotal accounts than research. On the online platform WeedMaps, the top effects for specific weed strains like Northern Lights (“Relaxed,” “Sleepy”) are crowdsourced from hundreds of user reviews — a stoned person’s idea of a clinical trial.

The cannabis industry’s reliance on this form of research is the byproduct of federal prohibition, which has rendered cannabis research almost comically cumbersome. Before 2020, just one growing facility in Mississippi was authorized to grow weed for FDA-approved studies, and scientists were required to store their stashes in DEA-approved vaults.

We are still in the early stages of demystifying this holy plant. Researchers have discovered that cannabis contains over 500 compounds, including 140 cannabinoids with some degree of psycho-pharmacological activity. That is to say: any old weed strain has ten times more active ingredients than a pharmaceutical like, say, Prozac. While THC and CBD are the most well-known, scientists are still unpacking how rarer cannabinoids like CBG, THCV, and CBN interact with the plant’s terpenes and flavanoids — compounds that give weed its rich smells and flavors — to produce a compound high known as the “entourage effect.” Further complicating matters, a cannabis plant’s chemical makeup can also differ wildly depending on growing conditions; the same strain could produce different levels of cannabinoids and terpenes depending on factors like climate, weather, and soil.

As we decode weed’s cryptic chemistry, we are also learning a lot about its coevolutionary relationship with humanity. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Raphael Mechoulam, the “father of cannabis research,” discovered that the human body produces its own endogenous cannabinoids, known as endocannabinoids, which help to regulate critical functions like learning, sleep, pain, immunity, and stress. This could explain the bewildering variety of behavioral and psychological effects of cannabis on our bodies, and why this complex plant remains such a mystery. Thus, products that claim they can customize the properties of weed to induce specific feelings are more often creating an illusion of control over a highly individualized and unpredictable experience, distilling the ambiguity of cannabis into a consumer choice: it all depends on finding the right product for you.

As we decode weed’s cryptic chemistry, we are also learning a lot about its coevolutionary relationship with humanity.

But what if we could hack the cannabis plant to deliver that customizability? Scientists have been harnessing DNA technology to sequence the cannabis genome and create genetically-engineered strains that are not just more productive and hardy, but could one day deliver the targeted experiences that consumers, investors and farmers are craving. Biohacking weed might sound surreal, but it’s already happening. In 2019, New Mexico-based biotech company Trait Bioscience debuted the world’s first genetically-modified cannabis plant. The transformed plant can produce cannabinoids like THC and CBD throughout its stems and leaves, not just its flowering buds, thus making it more productive — and profitable. Another superpower the mutant plant possesses: its cannabinoids are water-soluble, making them ideal for creating weed drinks (traditional plant cannabinoids are fat-soluble, and usually require a process of emulsification to disperse them in water).

Companies like StrainGenie, Endocanna Health, and Dynamic DNA Laboratories go even further, sending at-home DNA tests to consumers, and purporting to use that data to recommend customized doses, products, and strains that are most compatible with their genetic profiles. Endocanna, which markets itself as “the future of personalized cannabinoid therapeutics,” charges $199 for their services. (Users can send in existing tests from services like 23andMe for a smaller fee.) The company recently partnered with California cannabis brand Sunderstorm to launch a line of tinctures that will be tailored to match individual customers’ DNA results. These companies are leaning into the allure of “precision medicine,” a medical approach that optimizes therapeutic benefits for patients through customized genetic or molecular profiling.

Commercial interest in these futurist strategies is already heating up: In 2018, for example, Canadian cannabis conglomerate Canopy Growth paid more than $300 million to acquire Ebbu, a small Colorado-based biotech company that pioneered manipulating the cannabis genome with the gene-editing tool CRISPR–Cas9. The company specializes in creating single-cannabinoid strains, such as plants that only produce CBG. Ebbu’s CEO Jon Cooper said in a statement, “We believe this groundbreaking work will result in the most consistent and predictable products in the industry.”

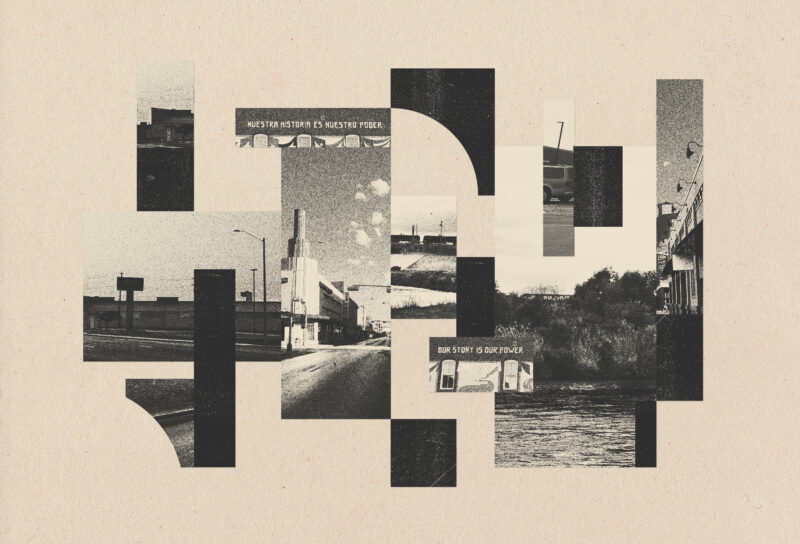

Genetically-modified weed could increase the drug’s pharmaceutical potential and its ability to be patented, thus boosting its allure to Big Pharma — nevermind the generations of Indigenous cultures who farmed cannabis, people who have gone to prison for selling or using it, and other stewards of this plant. That none of these communities will benefit from their contribution to this millenia-long project — or if anyone can even own a strain of marijuana — is largely irrelevant to the pharma patent system, where the winner takes all. As Trait’s Chief Strategy Officer Ronan Levy told Extraction Magazine: “The biggest knock on most products that exist right now is the lack of predictability of experience … As progress moves forward in this respect, we expect that Big Pharma will start to make active investments in the industry, which we think they would be smart to do.”

But as we edge towards weed’s biosynthetic future, are we arriving at something genuinely cool — or could this be the next bubble of overpromise?

Knowable Plants

The attempts to demystify our favorite past-time raise epistemological questions about the knowability of plants to humans. The original stewards of cannabis developed it over generations — sampling, crossbreeding, and repropagating the ones with traits they most enjoyed. Today’s industry wants to identify every active compound and deconstruct the work done over millennia by farmers, using genetic data to create unique plants that meet a variety of needs . This may also make it easier for companies to navigate the byzantine legal structure around cannabis in the U.S.

The same week as Hall of Flowers, I attended another cannabis conference on the opposite end of the cool spectrum: a research convention called CannMed that draws top weed scientists from around the country. Located in a sleek business center in Pasadena, the hallways are full of bespectacled PhDs sporting polo shirts and laminated name-tags, sitting around eating packed lunches and discussing the latest cutting-edge weed science. Presentations have names like “Genomic Tools for Cannabis Sativa and Psilocybe Cubenis Propagation,” and “Exploring the Fascinating Development of Cannabinoid-Producing Trichomes in Cannabis Flowers.” Even the advertisements plastering the building’s walls read like educational texts: “In the bloom phase, cannabis devours MORE nitrogen, potassium, and zinc (and a tad more phosphorus) and uses LESS calcium iron manganese and boron,” reads one by Advanced Nutrients, a fertilizer company that claims to help cannabis plants reach their genetic potential.

Medicinal Genomics, the cannabis genetic company that organized the conference, claims it was the first to sequence the cannabis genome in 2011. While genomic breeding has been used in the agricultural industry for decades, due to restrictive legislation under prohibition, the first crude map of the weed genome was only published in the 2010s — a feat that allowed scientists to delve deeper into how exactly cannabis plants inherit their chemical profiles. By cross-breeding a hemp plant with the popular strain Purple Kush, researchers began to unravel one of the biggest mysteries in weed science: how hemp and marijuana evolved as separate strains with distinct chemical properties, even though they belong to the same species Cannabis sativa. Mapping the cannabis genome suggested that the ancient cannabis plant’s DNA were colonized by viruses millions of years ago, which drove the divergence of its gene sequences into THCA in marijuana and CBDA in hemp.

In the past five years, our understanding of the cannabis genome has become increasingly complex, thanks to new technologies and a loosening of U.S. federal regulations that allow researchers to handle cannabis DNA. Recent studies using genetic sequencing have helped to unravel the plant’s evolutionary history, including the finding that early cannabis domestication came from East Asia and modern-day China — not the Middle East, as popular cannabis mythology goes. Genomics is also helping scientists to artificially synthesize rare cannabinoids found in the weed plant, like CBC and THCV, by infusing cannabis genes into yeast cells, thus bypassing the plant completely.

Medicinal Genomics offers several services to growers, including the ability to sequence their plants’ genomics. This data allows breeders to verify that they are growing their selected strains, determine these strains’ rarity, and even build a case for IP protection. “To date, the vast majority of cannabis breeding has been really traditional,” Mike Catalano, Head of Genomics Services at Medicinal Genomics, tells me. “Having a genomic sequence of your plant allows you to show a DNA fingerprint of what you have, and cultivators are looking to create unique profiles that meet different needs — including increasing yield and resistance to pests and disease.”

The original stewards of cannabis developed it over generations — sampling, crossbreeding, and repropagating the ones with traits they most enjoyed.

I slip into a dimly-lit auditorium where a sociologist turned cannabis breeder named Seth Crawford is giving the keynote presentation. Using advanced DNA tools like the PAC Bio Sequel II sequencer, Crawford and his team at OregonCBD have been mapping the cannabis genome and working with research institutions like Oregon State University’s Global Hemp Innovation Center to share their findings. As I sit in the dark, scribbling notes on “phased diploid genome assemblies” and “stem-cell pangenomics,” it feels as if I’m surveying the biofuturist techscape of cannabis’ mutant future.

“Genome sequencing as a field has made some pretty radical advances in the last two to three years that have transformed the entire discipline,” Crawford later explains over the phone, as tractors from his hemp farm in Oregon roar in the background. “Cannabis is basically entering into legality at the same time as these technologies are becoming available. So what that’s doing is allowing us to rapidly accelerate the timeline on cannabis breeding, getting it up to speed with other modern crops.”

However, Crawford notes, “It’s not like genomic sequencing is going to suddenly make the plant totally predictable in every instance. The underlying reality is that just because a plant has a gene doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to predictably have the same chemical profile every single time. That one is always going to be up in the air.”

Excavating the plant’s most intimate genomic architecture could be particularly useful for the hemp industry. This is because, per the 2018 Farm Bill, legal hemp cannot contain more than 0.3% THC, and crops that test over the legal limit are routinely destroyed, resulting in crushing financial losses to growers. According to the Department of Agriculture, 42% of hemp crops in 2022 were found non-compliant with the testing requirement. Plant genetics could help alleviate this issue by allowing breeders to rapidly screen seedlings for THC levels, rather than waiting for plants to go through their entire life cycles.

“Our goal is to make plants predictable for farmers,” said Crawford. “We’re taking plants that we’ve identified through selective inbreeding, sequencing those, and then trying to get a deeper understanding of what’s going on in those plants that make them desirable in the first place.”

The world’s food crops have been ruthlessly screened and bred over generations for genetic properties like resistance to droughts, pests, and changing temperatures. As a result, today’s crops are more resilient and productive, but genetic diversity has also shrunk by 75% in the 20th century in favor of single, well-defined monocultures. I ask Catalano if cannabis could someday suffer the same fate: “One of the greatest strengths of this plant is the unbelievable diversity that it expresses, but it’s a possibility that we could be breeding towards a monoculture, especially if folks are trying to optimize for the same set of conditions.” He pauses, then adds, “I don’t think we’re there yet though.”

After Crawford’s keynote speech, I slip my notebook back into my backpack and wander through the convention center, scoping the hodgepodge of cannabis culture unfolding in the building’s maze of hallways. A scrum of cameramen for the upcoming reality show “High Science” — brought to you by the same TV crew as “Ice Road Truckers” and “Most Dangerous Catch” — scurry after cannabis scientists as if they were tailing hotshot celebs. Next to the coffee stand, the stoner-bro host of podcast Cannabis Talk 101 interviews two weed nurses, propping his foot up on the table and rattling off questions with the macho bluster of a sportscaster. In the exposition hall, jars of soil fertilizers for growing weed are displayed next to beauty products like a “bio-restorative crème” infused with cannabis oil and gold (apparently these scientists are still susceptible to the seductions of stoner decadence).

At the end of the furthest hallway, I run into Jeff Chen, a bright-eyed rock star in this burgeoning field. At age 29, Chen earned his chops as the founder of UCLA’s Cannabis Research Group — one of the world’s first university programs dedicated to cannabis. There, he and his team of 40 researchers analyzed both the benefits and health risks of medical cannabis, delving into critically understudied topics like the drug’s impact on adolescent brains, Alzheimer’s, and opioid use disorders.

As we strike up a conversation, Chen shares that he grew frustrated with the lingering barriers to cannabis research during his academic tenure. Describing cannabis as “arguably the most difficult substance to study in America,” he lists the myriad of restrictions that scientists still contend with — down to the type of weed they’re allowed to use in their work, which comes from that single government-approved facility in Mississippi, and does not chemically resemble the pot consumed today. The biggest issue, he says, is the lack of funding for clinical trials; federal grants are nearly impossible for Schedule I drugs, and pharmaceutical companies only fund research into proprietary cannabinoid formulations so they can bogart the market.

“The Pharma clinical trial model doesn’t really apply to cannabis, because you only invest millions in trials if you can patent and monopolize something,” Chen explains. “So [cannabis] is a democratized product that people are seemingly getting significant benefits from, but the data is relatively lacking.” In 2021, Chen left UCLA to start Radicle Science, a health-tech company that recently examined over a dozen CBD brands to determine whether their health claims correlate to user experiences, shipping products to participants who reported their effects through online surveys.

Chen’s work at UCLA and Radicle Science has made him especially adept at separating fact from fiction in a cannabis market rife with pseudoscientific claims. When I tell him about the product trends I noticed at the conference in Palm Springs, he laughs. “Effects-based marketing is largely a myth,” he says. “The cannabis industry has done a good job figuring out how to cultivate and extract cannabis, but doesn’t have much information on the effect of cannabinoids on the human body. That requires clinical trials, sophisticated knowledge, and equipment that Pharma and universities will not touch.”

According to Chen, the cannabis industry is still a long way off from using DNA testing to customize weed products. Genetic sequencing currently has a very limited use in the broader healthcare space, he continues, and is mostly applied for attacking certain types of cancer. “Outside of that, we’re not really using DNA in any widespread clinical setting,” he says. “So the odds that the cannabis industry has somehow figured this out is pretty low.” However, Chen posits that biosynthetic cannabis compounds — created by inserting cannabis genes into yeast — will be especially attractive to pharmaceutical companies, who will spend millions of dollars getting these costly products approved by the FDA and thus covered by insurance.

Chen also notes that genetically modified cannabis could be more environmentally sustainable in the long-run. “People are worried that GMO products might be harmful for human health, but keep in mind that if it uses less water, pesticide or fertilizer, the carbon footprint is dramatically reduced,” he says. “That’s a fair trade-off, and these are the questions we will have to grapple with as a society going forward.”

DNA hacking the cannabis plant may yield all manner of practical benefits. But, if the plan for predictable, customized highs works out, would weed even still be fun? For some of us, drugs are exciting and intimate experiences precisely because they’re not predictable, commodifiable sensations. Perhaps one day, our yearning for the mysteries of weed will just be another misplaced nostalgia elided by a new class of designer drugs. The cannabis plant — broken down into its components and reverse engineered from the molecule up — might not even be the same thing to the generations after us, but rather a Ship of Theseus sailing into the unknown (and perfectly stoned) future.