In the middle of the pandemic, when everything was shutting down, David Zilber chose to scale up. The wunderkind fermentation chef (author of the fermentation bible, The Noma Guide to Fermentation) left his job at arguably the world’s best restaurant to become a food scientist at one of the world’s biggest food corporations — Chr. Hansen. His culinary experiments once went straight from lab-to-table, reaching hundreds of guests a day. Now the turnaround is complicated by international laws and supply chains, but his recipes feed millions. We sat down with Zilber to find out why he chose to expand the scope of his experiments, how scaling up his work has influenced his unique process, and what this has revealed to him about the future of food.

Tell us about your work at Chr. Hansen. What do you do with your days?

Zilber: It’s kind of ironic: I work for this giant company — one of the biggest in food fermentation in the world — but I primarily work alone. Chr. Hansen’s main headquarters [outside Copenhagen], where the hardcore research and development labs are, is right across the street from me. They chose to kick me across the road so I would have free rein to cook with whatever microbes I want, without filling out a six month long application to avoid cross-contamination. I have this lovely kitchen here where I get to experiment with all sorts of things. There’s no average day; this was the same for me at Noma, where no two days were alike. Except the pace of Chr. Hansen is slower. So maybe there’s no two weeks that are alike in this case.

Why did you make the switch?

I was burnt out when the pandemic hit. It was the first time where the mission seemed fallible. In the week leading up to lockdown, flights were being canceled left and right. A big portion of Noma’s clientele fly into Denmark just to eat. Suddenly, there were like 50 cooks wandering the halls looking for something to do because we only had like 20 guests that lunch. All of a sudden, the improbable proposition of food as luxury art dawned on me. Is this something I’m going to do for the rest of my life? Suddenly I had the downtime to really think about it.

I wrote an open letter that said: ‘Hey, I’m done cooking, plug me into the food system. Let’s see what I can do.’ I kind of call myself a plumber. We need more chefs to get in between the source and the output and work on the pipes and figure out how to tighten up efficiencies, how to inject flavor, how to make the whole thing more sustainable without losing palatability. In this case, shouting out into the void actually worked.

What does your work look like in practice these days?

I feel like it’s a bit unwieldy — the power I might have. I sit between the microbiologists on production teams producing these bacteria — deciding what bacteria need to be grown for what purposes — and the companies that actually use them. I tell them how I think their food should taste and I prototype their recipes using bacteria. This isn’t food as luxury art; it’s food as necessity.

How does it help to have a chef in the equation?

If you want to achieve a longer shelf life but you don’t like that it’s giving you sour notes, you need to change your recipe. I’m going to tinker in what you’re doing.

Say you’re trying to take chemical preservatives and E numbers [food additives] out of your hummus, but you don’t want to create more food waste by having a hummus with no preservatives being thrown out every five days in a grocery store instead of two weeks. These are real, real problems for food manufacturers and food pacakge and also distributors like grocery stores. I’m going to suggest: Let’s try and put a bacteria in there that’ll overtake the endogenous flora. We know who this player is; what sort of flavors they produce, how active they are at refrigerated temperatures. But nonetheless, life has to live. So if a little bit of acid is produced, or you see some interaction with whatever fats are in the matrix, I get to come in and try to tweak things. How can we use this to our advantage? What do we have to do to the recipe to make it better? How can we ferment the chickpeas with a proteolytic bacteria to create more umami and thus balance the acids produced in a week’s time? Can we try to dream pie-in-the-sky and make a chickpea miso that you’re going to fold in just to make this more delicious off the bat? You slowly edge towards solutions this way.

What problems are you working on now?

I’m currently helping a seaweed farm in Norway preserve their harvest because they had a huge crop loss last year. These are crops that are being grown for animal feed that are more sustainable than chopping down forests to grow soy. Generally, the companies that I’m interfacing with are trying to find more sustainable ways to make the world better, which I think is a really cool aspect of my job. I’m troubleshooting solutions with that seaweed farm in an effort to preserve metric tons upon metric tons of seaweed in two months’ time. And it’s about being able to find the right bacteria to be able to do it.

Is preservation most often what drives your clients to want fermentation?

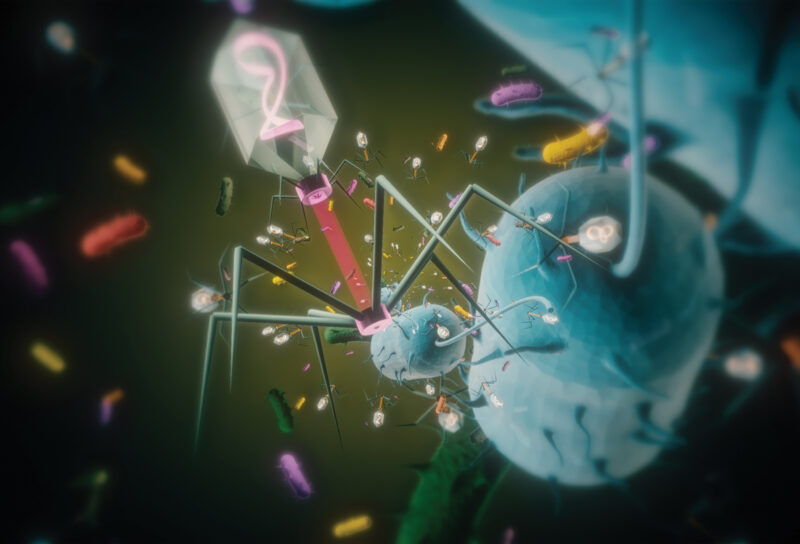

Chr. Hansen has bet on something called bio-protection. It’s effectively the addition of live culture to a finished product to replace preservatives. This might sound weird like, why are you adding organisms to our finished food, even in things like salad, but this is essentially what fermentation has always done. It’s just a targeted and precise application of that ability.

This isn’t food as luxury art; it’s food as necessity.

How’s your daily life changed with the new job?

In every way. It is the sharpest, black and white contrast imaginable, going from the world’s best restaurant to the world’s biggest fermentation company. You know, it can kind of feel like a large cargo ship when you’re used to driving a very nimble car. So steering it in new directions definitely takes time. But the flip side of that is that when you deliver your cargo, you’re delivering kilotons upon kilotons of food. When projects are completed, a month later, it’s like, “Hey, David, your recipes in every grocery store in Europe.” So that’s the difference. It’s a trade off.

How are the crowds you interact with on a daily basis different?

[Laughs.] Generally people are more proper. Cooking is a young person’s game. I was 34 when I quit Noma. And my back was feeling it. I couldn’t imagine still being there and pulling 16 hour days. There are benefits to going to the other side, I will say that. I’d say I get better sleep, but I also just had a kid. So actually I get worse sleep.

Now that you’re working at this massive scale: How do you see fermentation’s role in future-proofing global food systems?

I don’t know that fermentation can future-proof the world’s food systems. It comes in after the fact; you have to grow the food first. That being said, Chr. Hansen has a plant and animal health division that works directly with farms to do that same thing I was talking about with hummus. You take out chemical additives, you put bacteria into the equation. You can do the same thing for a field. You can take out chemical pesticides, spray plants with bacteria and see similar effects.

I will say that our ability to ferment is — if not a panacea, it’s at least an airbag. I think fermentation is something that we will fall back on and do probably more, should times get hard due to climate change. I think we’ll find ways to grow what we can and then preserve it as much as possible, using the microbes that have been with us this whole time. And that’ll force people’s taste to change, but so be it.

In synbio, there’s a competing discourse about our relationship to microbes. Should we be trying to dominate the organisms or cooperate with them? What’s your philosophical vantage point on the microbes you work with?

I always see it as a pact. Like a cooperative effort. Generally when humans try to dominate anything in nature, it goes badly for us eventually. And I think we’re learning that lesson now. I’m really anathema to this idea of dominating life to get what you want out of it. That just reeks of the worser demons of our nature, and then we just kind of shovel off the consequences onto the rest of the living world.

Whenever very crucial experiments or production would go wrong at Noma, I was always reminded that I’m not in control of these processes. I can bleach my incubation chambers all I want, I can sanitize as much as I want. But I’m not the one in charge of the transformation. The microbes are. I’m but a shepherd.

When you think about the next 150 years of fermentation, what does it look like to you for the process to improve?

I don’t think you can. Have you ever tasted a REALLY good pickle? It’s already perfect. How do you improve upon perfection? Of course, we could talk about transgenic organisms. I don’t necessarily think of that as an improvement, I think of it as something else. We could turn the microbes that we have been most friendly with for the longest amounts of time into our bespoke tailors, if you will, for organic molecules. You know, custom-built life. That has huge potential, because the footprint of a fermentation process is way less than the equivalent of a full grown adult mammal wandering somewhere in a field. The thing we’re set to lose is biological diversity, nutritional diversity.

Do engineered organisms endanger that “pact,” as you see it?

The consequences look like an unknown unknown. There’s a lot to win, but there’s also a lot to lose, so we just have to tread cautiously. The diversity part is a real tangible one that I experience. Italy has 250 different types of salami that are basically named after all the villages where they came up; Charles de Gaulle famously said “How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?” There’s real microbiological diversity to all of these foods.

Transgenic organisms for precision fermentation could excrete animal proteins to take cows out of the picture; to take the acids from fruits or vegetables on massive plantations out of the picture. It’s just going to be different. Of course, it also might be necessary.

So there’s potential there. I don’t necessarily see that as an improvement. I see it as kind of a tangent. And it comes with its own kind of risks and rewards. How do I see fermentation improving in the next 150 years? The only way I can answer that question is to say that it would improve if more people knew how to do it using what nature’s already provided us with.

How could one democratize it in that way? What needs to happen for more people to have access to it?

That democratization is already underway. The internet has been a huge accelerant. On TikTok there are 22 year olds showing you how to make koji in 60 seconds flat. It’s already happening. We just need to keep that fire stoked to see it grow.

How has thinking about food systems on this huge scale influenced your view of food on the small scale, just like the food that you eat?

It makes me want to eat even less processed foods. There’s a saying, You’re not always supposed to see how the sausage is made. I was a butcher. Sure, making sausage might be grisly, but it’s a very honest process. When you look into published papers about the nutritional loss of putting soy protein isolate through a heated extruder — is this really as good for us as we think it is? It really makes me cling to the tenets of food harvested fresh from the earth, manipulated as little as possible. That’s probably the best way to eat. Period.

What impact do you hope your work has in the long-term?

I don’t have this desire to have a statue erected of me somewhere for discovering something that’s going to win a Nobel Prize. I’m not reinventing the wheel here. I’m just using things that people have been using for thousands of years and trying to do them in new ways. If I can inspire people to think more deeply about what they’re putting in their mouths, or how it got there — or whether they have to buy it themselves, or if they could make it themselves — I’ve convinced myself that that might leave the planet a bit better than I found it. And that’s what I’m gonna keep doing.